One hundred and fifty million years ago, the Solnhofen Limestones of Germany were covered in small islands and warm saltwater lagoons. Coral reefs flourished with crinoids, sponges, jellyfish, and crustaceans; Dragonflies buzzed above the water as small reptiles sunned themselves at the water’s edge. Pterosaurs and Archaeopteryx took to the skies, but there was trouble in this Jurassic paradise: Tropical storms would turn it into a pterosaur graveyard.

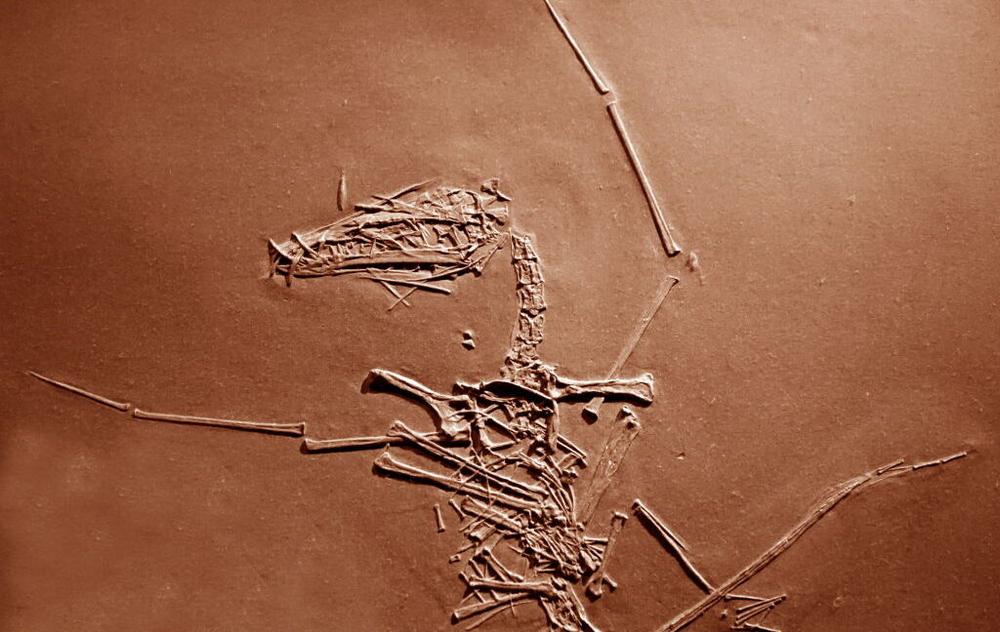

What paleontologist Rab Smyth found in this graveyard finally revealed why so many fledgling pterosaurs had succumbed to the storm. Smyth, a researcher at the Center for Paleobiology and Biosphere Evolution at the University of Leicester, unearthed two Pterodactylus antiquus hatchlings, and their bones showed exactly how they had succumbed to storm winds. The wings of both specimens (ironically named Lucky I and Lucky II) revealed clean, slanted humerus fractures that suggested they had been twisted in the storm. Unable to fly, they drowned and were rapidly buried in the lagoon depths.

“Our results show that most pterosaurs are preserved predominantly through catastrophic events, often reflecting mass mortality episodes,” Smyth and his research team said in a study he led, recently published in Current Biology.

Ancient autopsy

Solnhofen is a Lagerstätte, a region known for its exceptional preservation of fragile creatures that would have otherwise been lost to time. Anything that sank to the bottom of a lagoon was buried in soft carbonate muds that hardened into limestone over hundreds of millions of years. Many juvenile pterosaurs, thought to have been overpowered by storm winds before being plunged into the lagoons and covered in mud, had already surfaced at the site. What makes this new discovery so significant is that none of the previous finds showed any skeletal trauma.

Most of the pterosaur fossils found at Solnhofen are rather small. Long thought to belong to a smaller pterosaur species, they were later found to be juveniles of a larger species. That raises the question of how their delicate bones and soft tissues were preserved while larger casualties of the storm only left behind fragmented skeletons. Juveniles had hollow bones just like adults, but their bones were much more fragile and should not have held up easily under the weight of sediments. The expectation would be that the bodies of more robust adults would have stood a better chance of fossilization.

Smyth thinks that so few adults show up on the fossil record in this region not only because they were more likely to survive, but also because those that couldn’t were not buried as quickly. Carcasses would float on the water anywhere from days to weeks. As they decomposed, parts would fall to the lagoon bottom. Juveniles were small enough to be swept under and buried quickly by sediments that would preserve them.

Cause of death

The humerus fractures found in Lucky I and Lucky II were especially significant because forelimb injuries are the most common among existing flying vertebrates. The humerus attaches the wing to the body and bears most flight stress, which makes it more prone to trauma. Most humerus fractures happen in flight as opposed to being the result of a sudden impact with a tree or cliff. And these fractures were the only skeletal trauma seen in any of the juvenile pterosaur specimens from Solnhofen.

Evidence suggesting the injuries to the two fledgling pterosaurs happened before death includes the displacement of bones while they were still in flight (something recognizable from storm deaths of extant birds and bats) and the smooth edges of the break, which happens in life, as opposed to the jagged edges of postmortem breaks. There were also no visible signs of healing.

Storms disproportionately affected flying creatures at Solnhofen, which were often taken down by intense winds. Many of Solnhofen’s fossilized vertebrates were pterosaurs and other winged species such as bird ancestor Arachaeopteryx. Flying invertebrates were also doomed.

Even marine invertebrates and fish were threatened by storm conditions, which churned the lagoons and brought deep waters with higher salt levels and low oxygen to the surface. Anything that sank to the bottom was exceptionally preserved because of these same conditions, which were too harsh for scavengers and paused decomposition. Mud kicked up by the storms also helped with the fossilization process by quickly covering these organisms and providing further protection from the elements.

“The same storm events responsible for the burial of these individuals also transported the pterosaurs into the lagoonal basins and were likely the primary cause of their injury and death,” Smyth concluded.

Although Lucky I and Lucky II were decidedly unlucky, the exquisite preservation of their skeletons that shows how they died has finally allowed researchers to solve a case that went cold for over a hundred thousand years.

Current Biology, 2025. DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.08.006

Bambino apre ovetto Kinder e ci trova un drone russo

Bambino apre ovetto Kinder e ci trova un drone russo