In recent weeks, the secretive Chinese space program has reported some significant milestones in developing its program to land astronauts on the lunar surface by the year 2030.

On August 6, the China Manned Space Agency successfully tested a high-fidelity mockup of its 26-ton "Lanyue" lunar lander. The test, conducted outside of Beijing, used giant tethers to simulate lunar gravity as the vehicle fired main engines and fine control thrusters to land on a cratered surface and take off from there.

"The test," said the agency in an official statement, "represents a key step in the development of China's manned lunar exploration program, and also marks the first time that China has carried out a test of extraterrestrial landing and takeoff capabilities of a manned spacecraft."

As part of the statement, the space agency reconfirmed that it plans to land its astronauts on the Moon "before" 2030.

Then, last Friday, the space agency and its state-operated rocket developer, the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology, successfully conducted a 30-second test firing of the Long March 10 rocket's center core with its seven YF-100K engines that burn kerosene and liquid oxygen. The primary variant of the rocket will combine three of these cores to lift about 70 metric tons to low-Earth orbit.

These successful efforts followed a launch escape system test of the new Mengzhou spacecraft in June. A version of this spacecraft is planned for lunar missions.

On track for 2030

Thus, China's space program is making demonstrable progress in all three of the major elements of its lunar program: the large rocket to launch a crew spacecraft, which will carry humans to lunar orbit, plus the lander that will take astronauts down to the surface and back. This work suggests that China is on course to land on the Moon before the end of this decade.

For the United States and its allies in space, there are reasons to be dismissive of this. For one, NASA landed humans on the Moon nearly six decades ago with the Apollo Program. Been there, done that.

Moreover, the initial phases of the Chinese program look derivative of Apollo, particularly a lander that strikingly resembles the Lunar Module. NASA can justifiably point to its Artemis Program and say it is attempting to learn the lessons of Apollo—that the program was canceled because it was not sustainable. With its lunar landers, NASA seeks to develop in-space propellant storage and refueling technology, allowing for lower cost, reusable lunar missions with the capability to bring much more mass to the Moon and back. This should eventually allow for the development of a lunar economy and enable a robust government-commercial enterprise.

But recent setbacks with SpaceX's Starship vehicle–one of two lunar landers under contract with NASA, alongside Blue Origin's Mark 2 lander—indicate that it will still be several years until these newer technologies are ready to go. So it's now probable that China will "beat" NASA back to the Moon this decade and win at least the initial heat of this new space race.

To put this into perspective, Ars connected with Dean Cheng, one of the most respected analysts on China, space policy, and the geopolitical implications of the new space competition. He was also a researcher at the Heritage Foundation for 13 years, where he focused on China. (He was not involved with Project 2025.) Now “sort of” retired, in his own words, Cheng is presently a non-resident fellow at the George Washington University Space Policy Institute.

The implications of this for the West

Ars: How significant was the Lanyue lander demonstration? Does this indicate the Chinese space program remains on track to land humans on the Moon by or before 2030?

Dean Cheng: The Lanyue lander is significant because it's part of the usual Chinese "crawl-walk-run" approach to major space (and other scientific) projects. The [People's Republic of China] can benefit from other people's experiences (much of NASA's information is open), but they still have to build and operate the spacecraft themselves. So the test of the Lanyue lander, successful or not, is an important part of that process.

Note that the Chinese also this week had a successful static test of the LM-10, which is their lunar SLV (satellite launch vehicle). This, along with the Lanyue, indicates that the Chinese lunar program is pushing ahead. The LM-10, even more than the Lanyue, is significant because it's a new launch vehicle, in the wake of problems with the LM-5 and the cancellation of the LM-9 (which was probably their Saturn-V equivalent).

Ars: How likely is it that China lands humans on the Moon before NASA can return there with the Artemis Program?

Cheng: At the rate things are going, sadly, it seems quite likely that the Chinese will land on the Moon before NASA can return to the Moon.

Ars: What would the geopolitical impact be if China beats the United States back to the Moon?

Cheng: The geopolitical impact of the Chinese beating the US to the Moon (where we are returning) would be enormous.

Ars: How so?

Cheng: It means the end of American exceptionalism. One of the hallmarks of the post-1969 era was that only the United States had been able to land someone on the Moon (or any other celestial body). This was bound to end, but the constant American refrain of "We've put a man on the Moon, we can do anything" will certainly no longer resonate.

It means China can do "big" things, and the United States cannot. The US cannot even replicate projects it undertook 50 (or more) years ago. The optics of "the passing of the American age" would be evident—and that in turn would absolutely affect other nations' perceptions of who is winning/losing the broader technological and ideological competition between the US and the PRC.

A few years back, there was talk of "The Beijing Consensus" as an alternative to the "Washington Consensus." The Washington Consensus posited that the path forward was democracy, pluralism, and capitalism. The Beijing consensus argued that one only needed economic modernization. That, in fact, political authoritarianism was more likely to lead to modernization and advancement. This ideological element would be reinforced if Beijing can do the "big" things but the US cannot.

And what will be the language of cis-lunar space? The Chinese are not aiming to simply go to the Moon. Their choice of landing sites (most likely the South Pole) suggests an intent to establish longer-term facilities and presence. If China regularly dispatches lunar missions (not just this first one), then it will rightfully be able to argue that Chinese should be a language, if not the language, of lunar/cis-lunar space traffic management. As important, China will have an enormous say over technical standards, data standards, etc., for cis-lunar activities. The PRC has already said it will be deploying a lunar PNT (positioning, navigation, and timing) network and likely a communications system, (given the BeiDou's dual capabilities in this regard).

Ars: Taking the longer view, is the United States or China better positioned (i.e., US spending on defense, reusable in-space architecture vs Chinese plans) to dominate cislunar space between now and the middle of this century?

Cheng: On paper, the US has most of the advantages. We have a larger economy, more experience in space, extant space industrial capacity for reusable space launch, etc. But we have not had programmatic stability so that we are consistently pursuing the same goal over time. During Trump-1, the US said it would go to the Moon with people by 2024. Here we are, halfway through 2025. Trump-2 seems to once again be swinging wildly from going (back) to the Moon to going to Mars. Scientific and engineering advances don't do well in the face of such wild swings and inconstancy.

By contrast, the Chinese are stable, systematic. They pursue a given goal (e.g., human spaceflight, a space station) over decades, with persistence and programmatic (both budgetarily and in terms of goals) stability. So I expect that the Chinese will put a Chinese person on the Moon by 2030 and follow that with additional crewed and unmanned facilities. This will be supported by a built-out infrastructure of lunar PNT/comms. The US will almost certainly put people on the Moon in a landing in the next several years, but then what? Is Lunar Gateway going to be real? How often will the US go to the Moon, as the Chinese go over and over?

Ars: Do you have any advice for the Trump administration in order to better compete with China in this effort to not only land on the Moon but have a dominant presence there?

Cheng: The Trump administration needs to make a programmatic commitment to some goal, whether the Moon or Mars. It needs to mobilize Congress and the public to support that goal. It needs to fund that goal, but as important, it also needs to have a high-level commitment and oversight, such as the VP and the National Space Council in the first Trump administration. There is little/no obvious direction at the moment for where space is going in this administration, and what its priorities are.

This lack of direction then affects the likelihood that industry, whether big business or entrepreneurs, can support whatever efforts do emerge. If POTUS wants to rely more on entrepreneurial business (a reasonable approach), he nonetheless needs to provide indications of this. It would help to also provide incentives, e.g., a follow-on to the Ansari and X-prizes, which did lead to a blossoming of innovation.

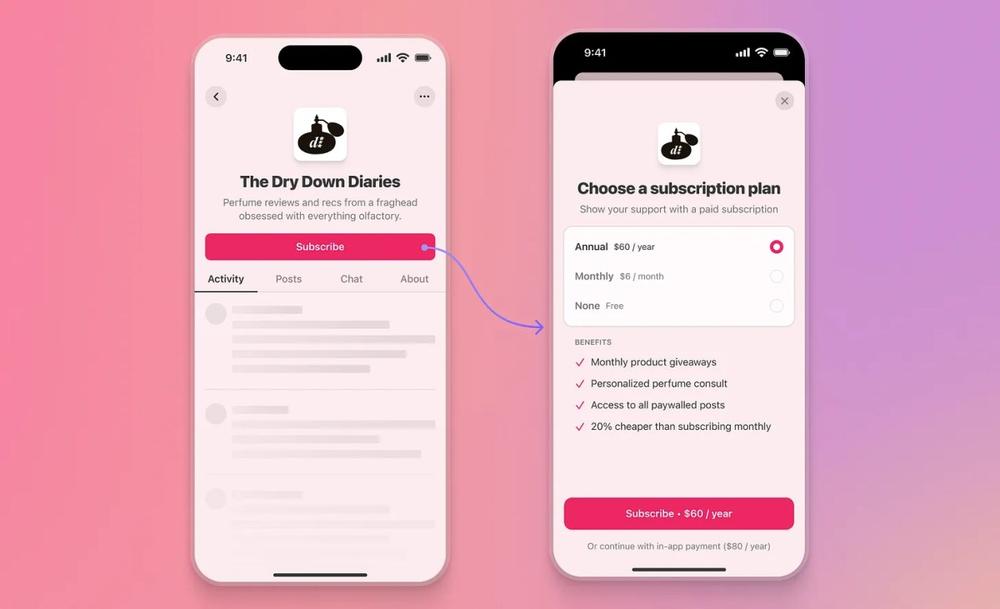

Substack writers can now direct US readers to (often cheaper) web-based subscriptions on iOS

Substack writers can now direct US readers to (often cheaper) web-based subscriptions on iOS