AI systems have recently had a lot of success in one key aspect of biology: the relationship between a protein’s structure and its function. These efforts have included the ability to predict the structure of most proteins and to design proteins structured so that they perform useful functions. But all of these efforts are focused on the proteins and amino acids that build them.

But biology doesn’t generate new proteins at that level. Instead, changes have to take place at the nucleic acid level before eventually making their presence felt at the protein level. And the DNA level is fairly removed from proteins, with lots of critical non-coding sequences, redundancy, and a fair degree of flexibility. It’s not necessarily obvious that learning the organization of a genome would help an AI system figure out how to make functional proteins.

But it now seems like using bacterial genomes for the training can help develop a system that can predict proteins, some of which don’t look like anything we’ve ever seen before.

Training a genome model

The new work was done by a small team at Stanford University. It relies on a feature that’s common in bacterial genomes: the clustering of genes with related functions. Often, bacteria have all the genes needed for a given function—importing and digesting a sugar, synthesizing an amino acid, etc.—right next to each other in the genome. In many cases, all the genes are transcribed into a single, large messenger RNA. This gives the bacteria a simple way to control the activity of entire biochemical pathways at once, boosting the efficiency of bacterial metabolisms.

So, the researchers developed what they term a “genomic language model” they call Evo on an enormous collection of bacterial genomes. The training was similar to what you’d see in a large language model, where Evo was asked to output predictions of the next base in a sequence, and rewarded when it got it right. It’s also a generative model, in that it can take a prompt and output novel sequences with a degree of randomness, in the sense that the same prompt can produce a range of different outputs.

The researchers argue that this setup lets Evo “link nucleotide-level patterns to kilobase-scale genomic context.” In other words, if you prompt it with a large chunk of genomic DNA, Evo can interpret that as an LLM would interpret a query and produce an output that, in a genomic sense, is appropriate for that interpretation.

The researchers reasoned that, given the training on bacterial genomes, they could use a known gene as a prompt, and Evo should produce an output that includes regions that encode proteins with related functions. The key question is whether it would simply output the sequences for proteins we know about already, or whether it would come up with output that’s less predictable.

Novel proteins

To start testing the system, the researchers prompted it with fragments of the genes for known proteins and determined whether Evo could complete them. In one example, if given 30 percent of the sequence of a gene for a known protein, Evo was able to output 85 percent of the rest. When prompted with 80 percent of the sequence, it could return all of the missing sequence. When a single gene was deleted from a functional cluster, Evo could also correctly identify and restore the missing gene.

The large amount of training data also ensured that Evo correctly identified the most important regions of the protein. If it made changes to the sequence, they typically resided in the areas of the protein where variability is tolerated. In other words, its training had enabled the system to incorporate the rules of evolutionary limits on changes in known genes.

So, the researchers decided to test what happened when Evo was asked to output something new. To do so, they used bacterial toxins, which are typically encoded along with an anti-toxin that keeps the cell from killing itself whenever it activates the genes. There are a lot of examples of these out there, and they tend to evolve rapidly as part of an arms race between bacteria and their competitors. So, the team developed a toxin that was only mildly related to known ones, and had no known antitoxin, and fed its sequence to Evo as a prompt. And this time, they filtered out any responses that looked similar to known antitoxin genes.

Testing 10 of the outputs returned by Evo, they found half were able to rescue some toxicity, and two of them fully restored growth to bacteria that were producing the toxin. These two antitoxins had only extremely weak similarity to known anti-toxins, at about 25 percent sequence identity. And they weren’t simply formed by pasting together a handful of pieces of known anti-toxins; at a minimum, they appeared to be assembled from parts of 15 to 20 individual proteins. In an additional test, the output would have been needed to have been patched together from parts of 40 known proteins.

Evo’s success wasn’t limited to proteins. When they tested a different toxin that had an RNA-based inhibitor, the system could output DNA that encodes RNAs with the right structural features, even if the specific sequence wasn’t closely related to anything known.

Completely new proteins

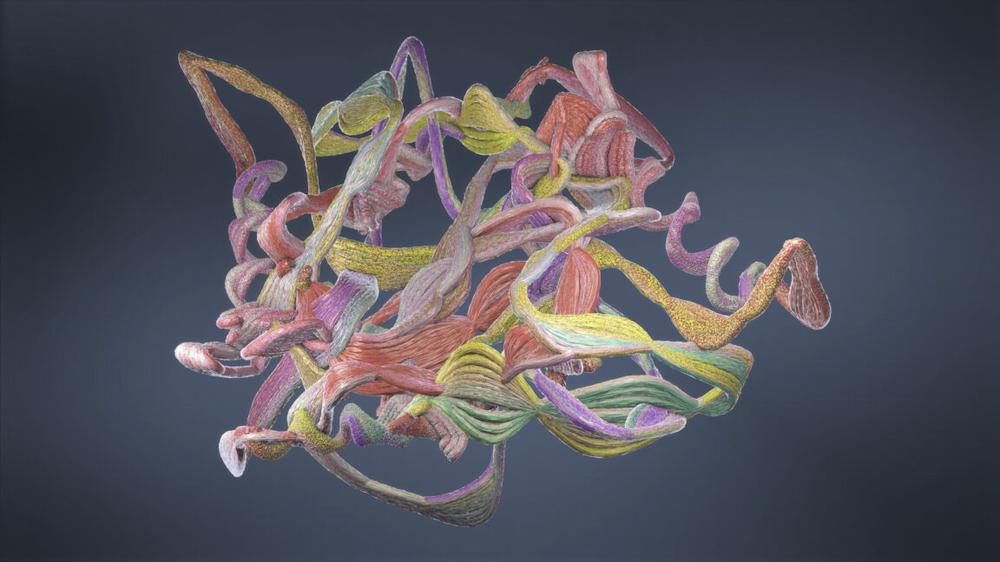

The team performed a similar test with inhibitors of the CRISPR system, which we use for gene editing, but bacteria evolved as a form of protection from viruses. The naturally occurring CRISPR inhibitors are very diverse, with many of them seemingly unrelated to each other. Once again, the team filtered the outputs to only include those that encoded proteins and filtered out any of those proteins that looked like something we already knew about. Of the list of outputs they made proteins from, 17 managed to inhibit CRISPR function. Two of those were distinctive in that they had no similarity to any known proteins and confused software that is designed to predict the three-dimensional structure of proteins.

In other words, along with the sorts of outputs you’d expect, Evo appears to be capable of outputting entirely new yet functional proteins. And it seems to do so without taking any consideration of the structure of the protein into account.

Given that their system appears to work, the researchers decided to prompt it with just about everything: 1.7 million individual genes from bacteria and the viruses that prey on them. The result is 120 billion base pairs of AI-generated DNA, some of it containing genes we already knew about, some of it presumably containing truly novel stuff. It’s not clear to me how anyone would productively use this resource, but I’d imagine there are some creative biologists who will think of something.

It’s not clear that this approach will work with more complex genomes, like the one we’ve got. Organisms like vertebrates mostly don’t cluster genes with related functions, and their genes have far more intricate structures that might confuse a system that’s trying to learn the statistical rules of base frequencies. And, to be clear, it solves different problems from the sort of directed design efforts that have developed enzymes that do useful things like digesting plastics.

That said, it’s still kind of amazing that this works at all. And conceptually, it’s intriguing because it brings the issue of finding functional proteins down to the nucleic acid level, where evolution normally does its thing.

Nature, 2025. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09749-7 (About DOIs).

We Build LEGO One Piece: Battle at Arlong Park

We Build LEGO One Piece: Battle at Arlong Park