A little more than a century ago, the US Army Air Service came up with a scheme for naming the military’s multiplying fleet of airplanes.

The 1924 aircraft designation code produced memorable names like the B-17, A-26, B-29, and P-51—B for bomber, A for attack, and P for pursuit—during World War II. The military later changed the prefix for pursuit aircraft to F for fighter, leading to recognizable modern names like the F-15 and F-16.

Now, the newest branch of the military is carving its own path with a new document outlining how the Space Force, which can trace its lineage back to the Army Air Service, will name and designate its “weapon systems” on the ground and in orbit. Ars obtained a copy of the document, first written in 2023 and amended in 2024.

The changes could ultimately lead to the retirement, or at least the de-emphasis, of bulky bureaucratic acronyms. You might think of it as similar to how the Pentagon’s Joint Strike Fighter program evolved into the F-35 Lightning II.

The memorandum outlining the Space Force’s new nomenclature was signed in 2023 by then-Lt. Gen. Shawn Bratton, who was the branch’s chief strategy and resource officer at the time. Bratton is now a four-star general serving as vice chief of space operations, the No. 2 uniformed position in the Space Force.

The document, titled Space Force Instruction 16-403, covers “Space Force weapon system naming and designations.” It provides guidance for creating new designators. The Space Force says compliance with the instruction is mandatory for new programs, but it does not require an update for existing satellites.

“All new weapon systems developed after the effective date of this instruction will require a designator,” the memorandum says. The new names will have letters identifying each system’s purpose and orbital regime, followed by numbers or letters describing its design number and design series.

John Shaw, a retired Space Force lieutenant-general, was part of internal discussions about revamping the military satellite naming scheme several years ago.

“We were looking at this in 2018, before we had a Space Force, and trying to fit it into the Air Force nomenclature,” Shaw told Ars. “And it sort of hit a dead end because the Air Force just wasn’t set up well for this. You really needed to start over. That wasn’t going to happen very easily. Now that we have a Space Force, we can start over… I’m glad to see that it’s becoming reality.”

Reforming the Byzantine

Many US military missions are currently known by several names. They can be confusing to anyone who isn’t steeped in Pentagon nomenclature.

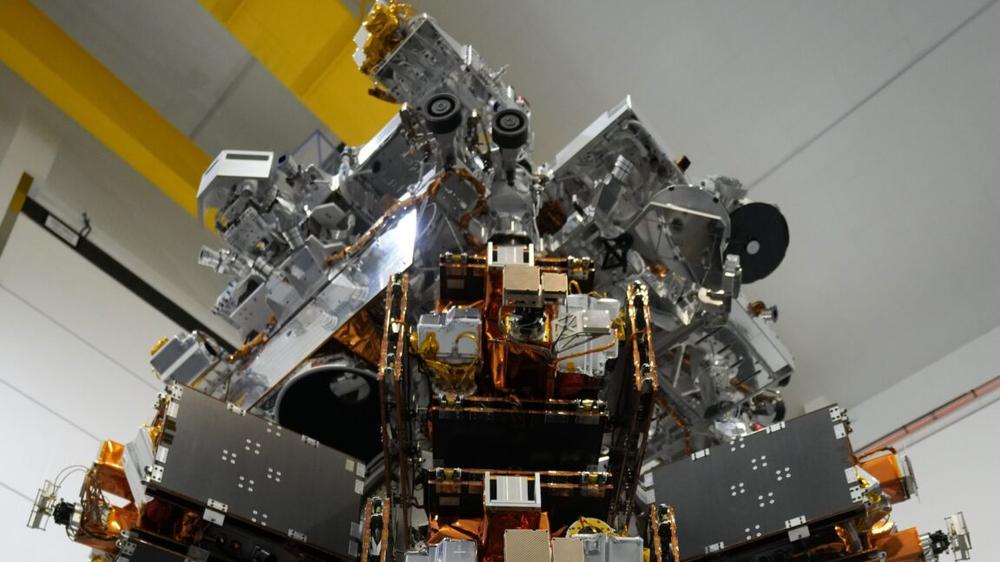

Let’s use one mission to illustrate this problem. In 2022, the Space Force launched the sixth in a series of satellites built for the Geosynchronous Space Situational Awareness Program (GSSAP). The satellite was known as GSSAP 6 before its launch. Once in orbit, the Space Force catalogued the spacecraft as USA-325, in keeping with the military’s sequential numbering scheme for national security satellites.

What’s more, the Space Force’s launch directorate designated the mission as USSF-8. These USSF numbers are generic descriptors for any rocket launch carrying Space Force-owned national security payloads.

So, why add another designation to the Pentagon’s Rolodex of satellite names? If used transparently, the nomenclature might provide clarity on which satellites are doing what missions. But this hasn’t always been the case for the military. For example, the Air Force used a fighter plane designation for the F-117 Nighthawk, when in reality, it was a stealth aircraft designed for ground attacks.

“I love the idea of getting a nomenclature,” said Shaw, whose final post before retirement was deputy commander of US Space Command. “I’m on record saying I don’t like the acronym GSSAP. It’s a horrible acronym. Even the word SAP (an acronym for highly classified Special Access Programs) makes it sound like it’s super secret.”

The military’s GSSAP satellites roam geosynchronous orbit, a ring more than 22,000 miles (nearly 36,000 kilometers) over the equator. In this orbit, satellites move around the Earth at the same rate as the planet’s rotation, giving them persistent views of entire continents.

Potential adversaries like China and Russia—along with the United States itself—position spy satellites, early warning platforms, and perhaps soon will place defensive and offensive weapons in geosynchronous orbit. The GSSAP satellites maneuver around geosynchronous orbit with cameras and sensors to see what other satellites are doing.

Most programs using the new naming scheme will have two letters, first describing the basic mission, and then its operating environment. The list is illustrative of the kinds of satellites the Space Force operates today or foresees deploying in the coming years. According to the Space Force memorandum, the basic mission designations are:

The Space Force also outlines optional modifiers to be placed before the required two-letter prefix. A test, experimental, prototype, or scientific and calibration version of a Space Force system would be preceded by the letters T, X, Y, or Z, respectively.

Some examples

So, the 12th missile warning satellite in a future series located in a highly elliptical orbit might be named WH-12. A future satellite in the GPS IIIF series in medium-Earth orbit might be designated NM-10F. And the 16th in a series of ground-based Bounty Hunter antennas designed to detect sources of radio interference affecting US military satellites could be called ET-16.

The Space Force’s replacement program for the GSSAP reconnaissance constellation is the first to publicly use the new designation guidelines. Military officials have previously disclosed the new program’s name, RG-XX, but its meaning has withstood scrutiny. It turns out, RG reveals that the next-generation satellites will perform a reconnaissance mission in geosynchronous orbit. The XX is a placeholder for a numbered series. Presumably, the first in the line will be named RG-01.

The RG-XX satellites will differ from the existing GSSAP platforms in a couple of important ways. First, the new RG-XX platforms will be refuelable in space, overcoming the GSSAP satellites’ limitations of a finite fuel supply, something that has troubled military commanders who would like to steer the satellites through space without worrying about running out of propellant. Second, the Space Force intends to buy the new recon satellites from multiple manufacturers, adding a layer of competition that officials hope will lower costs and yield a larger fleet in orbit.

Shaw, a longtime proponent of in-orbit refueling, said he was happy to see the Space Force taking this approach.

“It’s significant because that’s really the first time that the Space Force has said we want an operational platform to be refuelable,” Shaw said. “They haven’t talked about how they’re going to refuel it and who’s going to be a refueler. Everything else has been R&D or demos up to this point, but it’s a significant first step.”

Audio super prezzo ok. La prova dell'impianto Made In China che delizia l'udito

Audio super prezzo ok. La prova dell'impianto Made In China che delizia l'udito