AI bubble talk is in the air, and among the chorus of voices warning of an AI-fueled market bubble (which includes OpenAI CEO Sam Altman and Amazon's Jeff Bezos) is the Bank of England, which warned on Wednesday that global financial markets could face a sharp correction if investor sentiment turns negative on AI.

The UK central bank said US stock valuations resemble those seen near the peak of the dotcom bubble on some measures, with AI-focused companies making up an unprecedented portion of market value.

In its quarterly report derived from a meeting of its Financial Policy Committee that took place last week, BoE wrote that "the risk of a sharp market correction has increased." Reuters notes that it's the BoE's strongest warning to date about potential AI-driven market declines. The committee, chaired by Governor Andrew Bailey, said spillover risks to Britain's financial system from such a shock were "material."

The warning comes as the S&P 500 hit a record high on Tuesday, up 14 percent year to date. The BoE noted in its report that 30 percent of the S&P 500's valuation comes from just five companies at the top, which is the most concentrated the index has been in 50 years. These companies include chipmaker Nvidia, Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, and Facebook parent Meta, all of which have invested substantially in AI development.

Share valuations based on past earnings have also reached their highest levels since the dotcom bubble 25 years ago, though the BoE noted they appear less extreme when based on investors' expectations for future profits. "This, when combined with increasing concentration within market indices, leaves equity markets particularly exposed should expectations around the impact of AI become less optimistic," the central bank said.

Toil and trouble?

The dotcom bubble offers a potentially instructive parallel to our current era. In the late 1990s, investors poured money into Internet companies based on the promise of a transformed economy, seemingly ignoring whether individual businesses had viable paths to profitability. Between 1995 and March 2000, the Nasdaq index rose 600 percent. When sentiment shifted, the correction was severe: the Nasdaq fell 78 percent from its peak, reaching a low point in October 2002.

Whether we'll see the same thing or worse if an AI bubble pops is mere speculation at this point. But similarly to the early 2000s, the question about today's market isn't necessarily about the utility of AI tools themselves (the Internet was useful, after all, despite the bubble), but whether the amount of money being poured into the companies that sell them is out of proportion with the potential profits those improvements might bring.

We don't have a crystal ball to determine when such a bubble might pop, or even if it is guaranteed to do so, but we'll likely continue to see more warning signs ahead if AI-related deals continue to grow larger and larger over time.

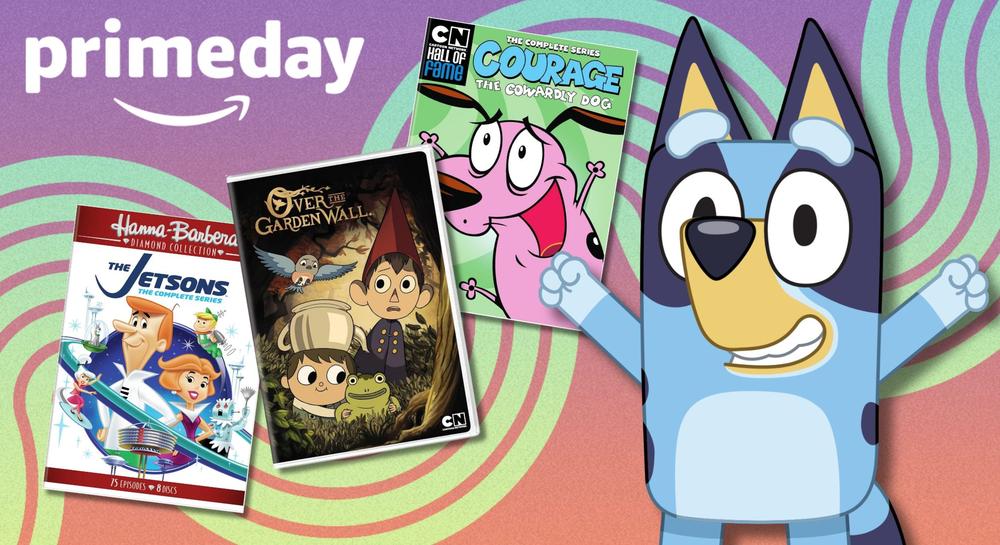

No Streaming Service Can Take Away the Cartoons You Get in Amazon's October Prime Day Deals

No Streaming Service Can Take Away the Cartoons You Get in Amazon's October Prime Day Deals