Last year, a group of researchers won the 2024 Ig Nobel Prize in Physiology for discovering that many mammals are capable of breathing through their anus. But as with many Ig Nobel awards, there is a serious side to the seeming silliness. The same group has conducted a new study on the feasibility of adapting this method to treat people with blocked airways or clogged lungs, with promising results that bring rectal oxygen delivery one step closer to medical reality.

As previously reported, this is perhaps one of the more unusual research developments to come out of the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated shortages of ventilators and artificial lungs to assist patients’ breathing and prevent respiratory failure. The Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center team took their inspiration from the humble loach, a freshwater bottom-dwelling fish found throughout Eurasia and northern Africa. The loach (along with sea cucumbers) employs intestinal breathing (i.e., through the anus) rather than gills to survive under hypoxic conditions, thanks to having lots of capillary vessels in its intestine. The technical term is enteral ventilation via anus (EVA).

Would such a novel breathing method work in mammals? The team thought it might be possible and undertook experiments with mice and micro-pigs to test that hypothesis. They drew upon earlier research by Leland Clark, also of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, who invented a perfluorocarbon liquid called Oxycyte as a possible form of artificial blood. That vision never materialized, although it did provide a handy plot point for the 1989 film The Abyss, in which a rat is able to “breathe” in a similar liquid.

And Oxycyte was ideal for the group’s 2021 Ig Nobel-winning efforts. The experiments involved intra-anally administering oxygen gas or a liquid oxygenated perfluorocarbon to the unfortunate rodents and porcines. Yes, they gave the animals enemas. They then induced respiratory failure and evaluated the effectiveness of the intra-anal treatment. The result: Both treatments were pretty darned effective at staving off respiratory failure with no major complications.

So far, so good. The next logical step was to determine if EVA could work in human patients, too. “Patients with severe respiratory failure often need mechanical ventilation to survive, but these therapies can cause further lung injury,” the authors wrote in this latest paper. EVA “could give the lungs a chance to rest and heal.”

The team recruited 27 healthy adult men in Japan, each of whom received a dose of non-oxygenated perfluorodecalin via the anus. They were asked to retain the liquid for a full hour as the dosage slowly increased from 25 to 1,500 mL. Twenty of the men successfully completed the experiment. Apart from mild temporary abdominal bloating and discomfort—which proved to be dosage dependent and resolved with no need for medical attention—they experienced no adverse effects.

“This is the first human data and the results are limited solely to demonstrating the safety of the procedure and not its effectiveness,” said co-author Takanori Takebe of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and the University of Osaka in Japan. “But now that we have established tolerance, the next step will be to evaluate how effective the process is for delivering oxygen to the bloodstream.”

DOI: Med, 2025. 10.1016/j.medj.2025.100887 (About DOIs).

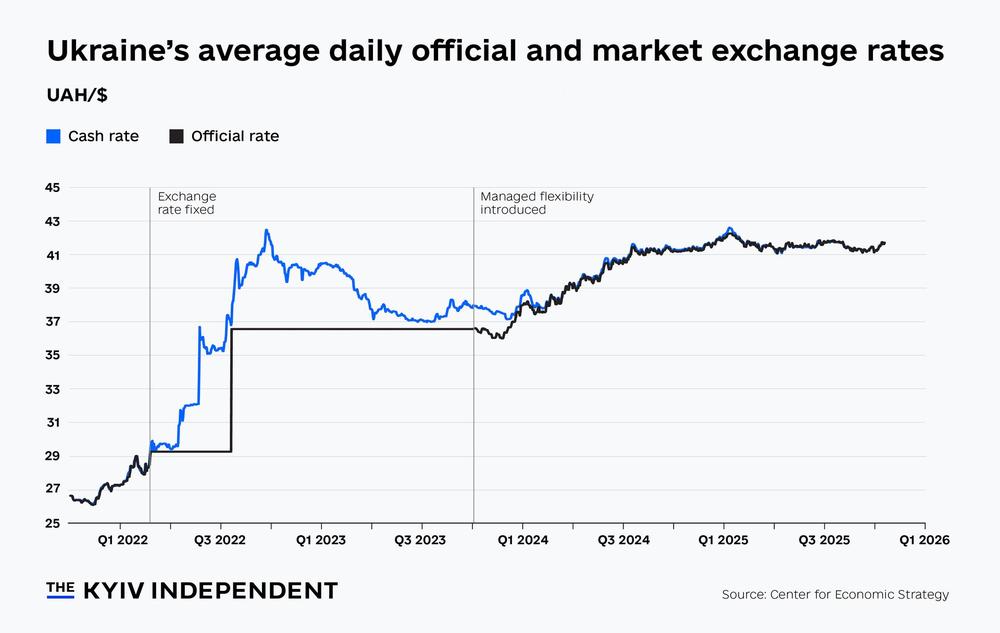

Chart of the week: Will Ukraine’s central bank weaken the hryvnia?

Chart of the week: Will Ukraine’s central bank weaken the hryvnia?