The pre-Inca Chincha Kingdom (circa 1000-1400 CE), along Peru’s southern coast, was one of the most wealthy and influential of its time before falling to the Inca and Spanish empires. Scientists have long puzzled over the foundation for that prosperity, and it seems one critical factor was bird poop, according to a new paper published in the journal PLoS ONE.

“Seabird guano may seem trivial, yet our study suggests this potent resource could have significantly contributed to sociopolitical and economic change in the Peruvian Andes,” said co-author Jacob Bongers, a digital archaeologist at the University of Sydney. “Guano dramatically boosted the production of maize (corn), and this agricultural surplus crucially helped fuel the Chincha Kingdom’s economy, driving their trade, wealth, population growth and regional influence, and shaped their strategic alliance with the Inca Empire. In ancient Andean cultures, fertiliser was power.”

Last November, Bongers co-authored a paper detailing evidence supporting the hypothesis that the mysterious “Band of Holes” on Mount Sierpe in the Andes might have been an ancient marketplace. Aerial photographs from the 1930s first revealed that long row of around 5,200 precisely aligned holes, seemingly organized into blocked sections, most likely constructed by the Chincha Kingdom. Scholars had suggested various hypotheses for what the site’s purpose may have been: defense, storage, or accounting, perhaps, or maybe to collect water and capture fog for local gardens. But nobody had any strong evidence for those suggestions.

Bongers conducted microbotanical sediment analysis of samples taken from the site and combined that data with new high-resolution aerial drone imagery. The former found traces of ancient maize pollens and reeds used in basket-weaving, indicating that the locals deposited plants transported in woven baskets or bundles into those holes. Bongers interpreted this as evidence of a pre-Inca marketplace where people exchanged local goods for the wares of mobile traders.

A nutrient-rich natural fertilizer

Now Bongers has turned his attention to analyzing the biochemical signatures of 35 maize samples excavated from buried tombs in the region. He and his co-authors found significantly higher levels of nitrogen in the maize than in the natural soil conditions, suggesting the Chincha used guano as a natural fertilizer. The guano from such birds as the guanay cormorant, the Peruvian pelican, and the Peruvian booby contains all the essential growing nutrients: nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. All three species are abundant on the Chincha Islands, all within 25 kilometers of the kingdom.

Those results were further bolstered by historical written sources describing how seabird guano was collected and its importance for trade and production of food. For instance, in colonial eras, groups would sail to nearby islands on rafts to collect bird droppings to use as crop fertilizer. The Lunahuana people in the Canete Valley just outside of Chincha were known to use bird guano in their fields, and the Inca valued the stuff so highly that it restricted access to the islands during breeding season and forbade the killing of the guano-producing birds on penalty of death.

The 19th-century Swiss naturalist Johann Jakob von Tschudi also reported observing the guano being used as fertilizer, with a fist-sized amount being added to each plant before submerging entire fields in water. It was even imported to the US. The authors also pointed out that much of the iconography from Chincha and nearby valleys featured seabirds: textiles, ceramics, balance-beam scales, spindles, decorated gourds, adobe friezes and wall paintings, ceremonial wooden paddles, and gold and silver metalworks.

“The true power of the Chincha wasn’t just access to a resource; it was their mastery of a complex ecological system,” said co-author Jo Osborn of Texas A&M University. “They possessed the traditional knowledge to see the connection between marine and terrestrial life, and they turned that knowledge into the agricultural surplus that built their kingdom. Their art celebrates this connection, showing us that their power was rooted in ecological wisdom, not just gold or silver.”

DOI: PLoS ONE, 2026. 10.1371/journal.pone.0341263 (About DOIs).

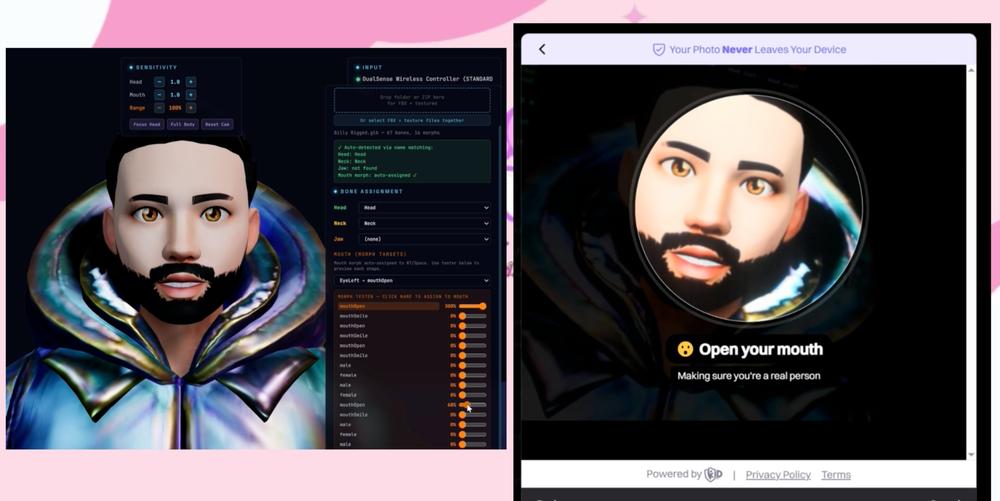

Free Tool Says it Can Bypass Discord's Age Verification Check With a 3D Model

Free Tool Says it Can Bypass Discord's Age Verification Check With a 3D Model