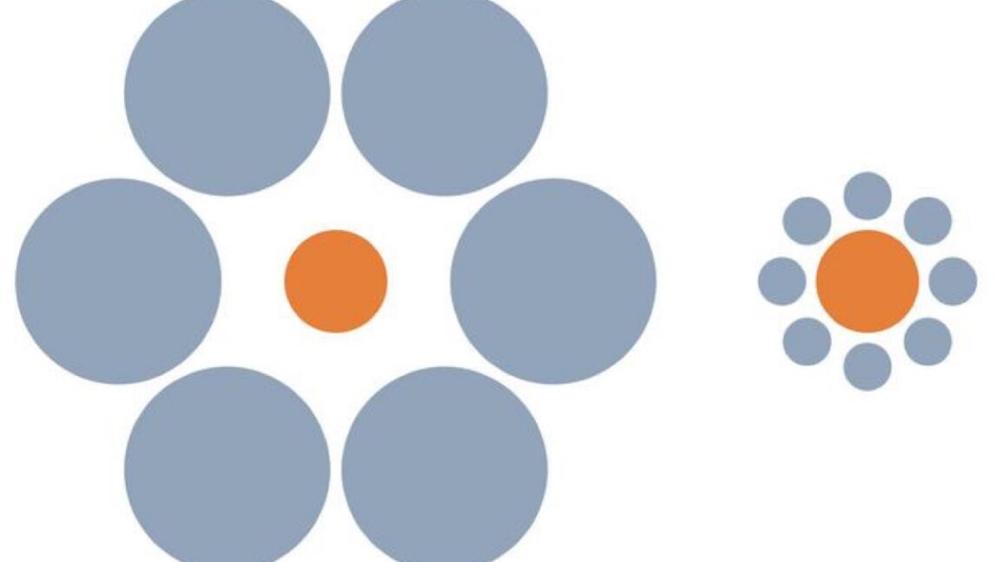

Chances are you’ve encountered some version of the “Ebbinghaus illusion,” in which a central circle appears to be smaller when encircled by larger circles and seems larger when surrounded by smaller circles. It’s an example of context-dependent size perception. But is this unique to humans or are some animals susceptible as well? According to a new paper published in the journal Frontiers in Psychology, it might depend on the specific sensory environment, since the illusion relies on contextual clues to be effective.

Prior research has produced mixed results on the question of animals and their susceptibility to optical illusions, per the authors. Dolphins, chicks, and redtail splitfins seem to be susceptible, for example, while pigeons, baboons, and gray bamboo snakes are not.

Perhaps the best-known example is cats’ undeniable love of boxes and squares—the “if it fits, I sits” phenomenon documented all over the Internet. This behavior is generally attributed to the fact that cats feel safer when squeezed into small spaces, but it also tells us something about feline visual perception. A 1988 study and a 2021 study concluded that cats are susceptible to the Kanizsa square illusion, suggesting that they perceive subjective contours much like humans.

The authors of this latest paper decided to test the Ebbinghaus illusion across two species that inhabit very different sensory environments: ring doves and guppies. The doves are terrestrial, pecking at small seeds scattered on the ground for food, so the authors reasoned that precision and attention to detail—rather than global processing to first analyze an entire scene, as humans do—would be more advantageous for the doves. Plus the doves have binocular vision and thus should be good at accurately judging size and distance.

Guppies, by contrast, live in the shallow waters of tropical streams. They must contend with dense vegetation, flickering light, and the unpredictability of predators. They must make rapid decisions in order to survive, and thus it would be advantageous for guppies to be able to judge relative size at a glance—a human-like global processing ability that is key to the Ebbinghaus illusion.

A tale of two species

The authors tested 38 ring doves and 19 guppies (of the “snakeskin cobra green” ornamental strain) for their experiments. The doves were placed in a testing cage with the bottom covered with an anti-slip wooden panel and a branch serving as a perch and starting point; the feeding station was at the opposite end of the cage. The guppies were tested in single tanks with a gravel bottom.

In both cases, the test subjects were presented with visual stimuli in the form of two white plastic cards. Sizes differed for the doves and the guppies, but each card showed an array of six black circles with a bit of food serving as the center “circle”: red millet seeds for the doves and commercial flake food for the guppies. The circles were smaller on one of the cards and larger on the other. The subjects were free to choose food from one of the cards, and the card with the unchosen food was removed promptly. If no choice was made after 15 minutes, the trial was null and the team tried again after a 15-minute interval.

The authors found that the guppies were indeed highly susceptible to the Ebbinghaus illusion, choosing food surrounded by smaller circles much more frequently, suggesting they perceived it as larger and hence more desirable. The results for ring doves were more mixed, however: some of the doves seemed to be susceptible while others were not, suggesting that their perceptual strategies are more local, detail-oriented, and less influenced by their surrounding context.

“The doves’ mixed responses suggest that individual experience or innate bias can strongly shape how an animal interprets illusions,” the authors concluded. “Just like in humans, where some people are strongly fooled by illusions and others hardly at all, animal perception is not uniform.”

The authors acknowledge that their study has limitations. For instance, guppies and ring doves diverged hundreds of millions of years ago and hence are phylogenetically distant, so the perceptual differences between them could be due not just to ecological pressures, but also to evolutionary traits gained or lost via natural selection. Future experiments involving more closely related species with different sensory environments would better isolate the role of ecological factors in animal perception.

Frontiers in Psychology, 2025. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1653695 (About DOIs).

This $20 Iniu 20,000mAh Power Bank Quadruples Your Nintendo Switch 2 Play Time

This $20 Iniu 20,000mAh Power Bank Quadruples Your Nintendo Switch 2 Play Time