If you’re in the space business long enough, you learn there are numerous ways a rocket can fail. I’ve written my share of stories about misbehaving rockets and the extensive investigations that usually—but not always—reveal what went wrong.

But I never expected to write this story. Maybe this was a failure of my own imagination. I’m used to writing about engine malfunctions, staging issues, guidance glitches, or structural failures. Last April, Ars reported on the bizarre failure of Firefly Aerospace’s commercial Alpha rocket.

Japan’s H3 rocket found a new way to fail last month, apparently eluding the imaginations of its own designers and engineers.

The H3 is a relatively new vehicle, with last month’s launch marking the eighth flight of Japan’s flagship rocket. The launcher falls on the medium-to-heavy section of the lift spectrum. The eighth H3 rocket lifted off from Tanegashima Island in southern Japan on December 22, local time, carrying a roughly five-ton navigation satellite into space.

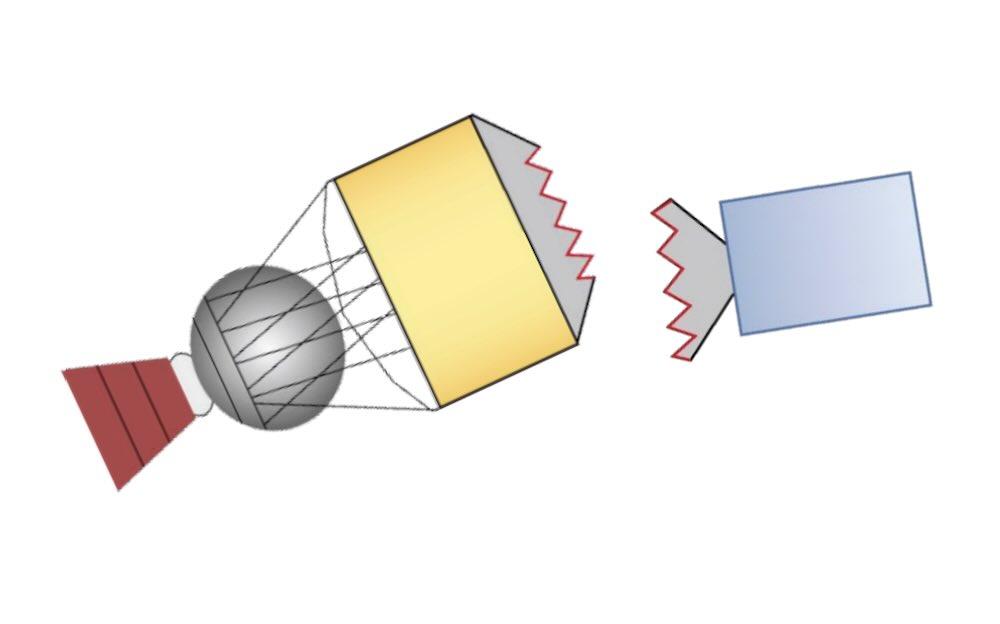

The rocket was supposed to place the Michibiki 5 satellite into an orbit ranging more than 20,000 miles above the Earth. Everything was going well until the H3 jettisoned its payload fairing, the two-piece clamshell covering the satellite during launch, nearly four minutes into the flight.

Officials from the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) are starting to get a handle on what happened. Agency officials briefed the government ministry overseeing Japan’s space activities last week, and the presentation (in Japanese) was posted on a government website.

The presentation is rich in information, with illustrations, a fault tree analysis, and a graph of in-flight measurements from sensors on the H3 rocket. It offers a treasure trove of detail and data most launch providers decline to release publicly after a rocket malfunction.

What happened?

Some of the material is difficult to grasp for a non-Japanese speaker unfamiliar with the subtle intricacies of the H3 rocket’s design. What is clear is that something went wrong when the rocket released its payload shroud. Video beamed back from the rocket’s onboard cameras showed a shower of debris surrounding the satellite, which started wobbling and leaning in the moments after fairing separation. Sensors also detected sudden accelerations around the attachment point connecting the spacecraft with the top of the H3 rocket.

At this point in the mission, the H3 rocket was well above the thick lower layers of the atmosphere. Aerodynamic forces were not a significant factor, but the rocket continued accelerating on the power of its two hydrogen-fueled main engines. The Michibiki 5 satellite held on for a little more than a minute, when the H3’s first stage shut down and separated from the rocket’s second stage.

The jolt from staging dislodged the satellite from its mooring atop the rocket. Then, the second stage lit its engine and left the satellite in the dust. A rear-facing camera on the upper stage captured a fleeting view of the satellite falling back to Earth. In the briefing package, Japanese space officials wrote that Michibiki 5 fell into the Pacific Ocean in the same impact zone as the H3’s first stage.

Whatever caused the satellite to break free of the rocket damaged more than its attach fitting. Telemetry data downlinked from the H3 showed a pressure drop in the second stage’s liquid hydrogen tank after separation of the payload fairing.

“A decrease in LH2 tank pressure was confirmed almost simultaneously,” officials wrote. A pressurization valve continued to open to restore pressure to the tank, but the pressure did not recover. “It is highly likely that the satellite mounting structure was damaged due to some factor, and as a result, the pressurization piping was damaged.”

The second stage engine lost 20 percent of its thrust, but it fired long enough to put the rocket into a low-altitude orbit. The rocket’s temporary recovery was likely aided by the absence of its multi-ton payload, meaning it needed a lower impulse to reach orbital velocity. The orbit was too low to sustain, and the second stage of the H3 rocket reentered the atmosphere and burned up within several hours.

Getting to root cause

Investigators now have a grasp of what happened, but they are still piecing together why. JAXA presented a fault tree analysis to the Japanese science and technology ministry, showing which potential causes engineers have ruled out, and which ones remain under investigation.

The branches of the fault tree still open include the possibility of an impact or collision between part of the payload fairing and the Michibiki 5 satellite or its mounting structure. Engineers continue to probe the possibility that residual strain energy in the connection between the satellite and the rocket was suddenly released at the moment of fairing separation.

The rocket is supposed to vent pressure inside the fairing as it ascends through thinner air and into space. Measurements from the rocket indicate the pressure inside the fairing decreased as expected during the launch. Officials don’t believe this was a factor in the launch failure, but engineers are examining whether the measurements were in error.

The rocket and satellite also carried combustible propellants, high-pressure gases, and pyrotechnics. “While no data indicating leakage of these substances has been confirmed, the possibility that they caused the abnormal acceleration cannot be ruled out at this time,” JAXA said.

So far, the probe has found no evidence that a structural problem with the satellite itself was the root cause of the failure.

With last month’s incident, the H3 rocket has a record of six successful launches in eight flights. The H3’s debut launch in 2023 faltered due to an ignition failure on the rocket’s second stage.

JAXA must complete the latest H3 failure investigation in the coming months to clear the rocket to launch the nation’s Martian Moons Exploration (MMX) mission in a narrow planetary launch window that opens in October. MMX is an exciting robotic mission to land on and retrieve samples from the Martian moon Phobos for return to Earth. MMX’s launch was previously set for 2024, but Japan’s space agency delayed it to this year due to earlier problems with the H3 rocket.

Volkswagen, Blume sotto pressione: Cina e software le sfide chiave per il suo futuro

Volkswagen, Blume sotto pressione: Cina e software le sfide chiave per il suo futuro