Sixty thousand years ago, two groups of Neanderthals lived just a stone’s throw apart in what’s now northern Israel. But they had very different cultures when it came to food, according to a recent study. Archaeologist Anaëlle Jallon of Hebrew University of Jerusalem and her colleagues examined dozens of animal bones from both sites, looking for clues about Neanderthal meal prep. It turns out that something as mundane as the cut marks left by butchering an animal can reveal differences in ancient people’s way of life.

What did Neanderthals eat? It depends.

The Neanderthals who lived around the Sea of Galilee between 70,000 and 50,000 years ago had their pick of meat entrees on the hoof. The area was home to several species of deer, from tiny roe deer to larger red deer, along with gazelles, wild goats, boar, and larger game like aurochs and relatives of modern horses. For Neanderthal hunters equipped with wood and stone hunting tools, the place was a veritable buffet. And you might expect that one group of Neanderthals would eat pretty much the same things as any others in the area.

However, what Jallon and her colleagues found in their recent study looks more like the Pleistocene version of New York and Chicago having very different styles of pizza: same ingredients, different ways of using them.

One group of Neanderthals lived in a cave now called Kebara on the western flanks of Mount Carmel, while the other lived in a cave now called Amud on a steep cliff overlooking the valley floor. They may not have lived at the same moment; the range of dates for both sites spans about 20,000 years. But both were just a few kilometers from the Sea of Galilee, living in very similar environments populated by the same plants and wildlife, and they used very similar stone tool technology.

Jallon and her colleagues looked at the piles of animal bones archaeologists have unearthed at both sites. They noted which bones, from which types of game, tended to show up with cut marks more often. They also noted how many cut marks the bones tended to bear and what those marks looked like. And their study revealed that Neanderthals just 70 kilometers apart were hunting slightly different prey and choosing different cuts of meat—and one group apparently liked their meat a little fresher than the other.

Gazelle prepared “a la Amud,” or “a la Kebara”?

Neanderthals at Kebara had pretty broad tastes in meat. The butchered bones found in the cave were mostly an even mix of small ungulates (largely gazelle) and medium-sized ones (red deer, fallow deer, wild goats, and boar), with just a few larger game animals thrown in. And it looks like the Kebara Neanderthals were “use the whole deer” sorts of hunters because the bones came from all parts of the animals’ bodies.

On the other hand (or hoof), at Amud, archaeologists found that the butchered bones were almost entirely long bone shafts—legs, in other words—from gazelle. Apparently, the Neanderthal hunters at Amud focused more on gazelle than on larger prey like red deer or boar, and they seemingly preferred meat from the legs.

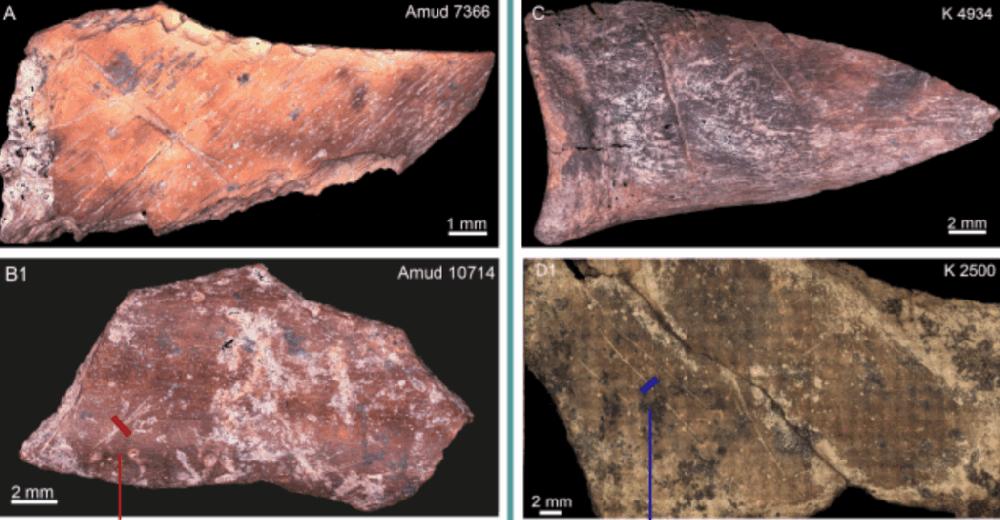

And not too fresh, apparently—the bones at Kebara showed fewer cut marks, and the marks that were there tended to be straighter. Meanwhile, at Amud, the bones were practically cluttered with cut marks, which crisscrossed over each other and were often curved, not straight. According to Jallon and her colleagues, the difference probably wasn’t a skill issue. Instead, it may be a clue that Neanderthals at Amud liked their meat dried, boiled, or even slightly rotten.

That’s based on comparisons to what bones look like when modern hunter-gatherers butcher their game, along with archaeologists’ experiments with stone tool butchery. First, differences in skill between newbie butchers and advanced ones don’t produce the same pattern of cut marks Jallon and her colleagues saw at Amud. But “it has been shown that decaying carcasses tend to be more difficult to process, often resulting in the production of haphazard, deep, and sinuous cut marks,” as Jallon and her colleagues wrote in their recent paper.

So apparently, for reasons unknown to modern archaeologists, the meat on the menu at Amud was, shall we say, a bit less fresh than that at Kebara. Said menu was also considerably less varied. All of that meant that if you were a Neanderthal from Amud and stopped by Kebara for dinner (or vice versa) your meal might seem surprisingly foreign.

Each group’s table manners may have been a little surprising to the other, too. Most of the animal bones at Amud were broken into fragments and appeared to have been burned, while most of the ones at Kebara were intact and unburned. That may suggest differences in cooking, or it may suggest differences in what people did with the bones after they’d cut all the meat off: tossing them in a corner of the cave instead of tossing them in the fire.

Again, the whole experience is perhaps a little like what New Yorkers must feel when they order a pizza in Chicago, or the other way around, or what Texans experience when they order brisket anywhere else.

Local tools for local cuisine

So two groups of Neanderthals managed to have strikingly different food cultures over a distance of just a few miles. And stone tools found in both caves suggest the cultural differences weren’t limited to eating habits.

Microscopic images of the cuts on butchered animal bones at both sites look similar, which suggests that the work was done with the same basic types of tools. And that’s mostly true; Neanderthals in both places used broadly similar techniques to make similar tools: triangular flakes and points, knapped from flint. Archaeologists who study stone tools, though, noticed some subtle differences that suggest Neanderthals at each site developed their own signature styles.

“The stone tools from Kebara and Amud show some technological variations interpretable as local traditions or accumulated through social learning,” Jallon and her colleagues wrote in their recent paper.

In other words, Neanderthals weren’t a cultural monolith (or a monolithic culture—not sorry). Their cultures were more complex and diverse than we’ve previously realized, and that shows up in subtle ways at different sites. It’s fascinating to speculate about how much more we could see about these extinct cultures if things like textiles, leather, and plants had survived better over millennia.

Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology, 2023 DOI: 10.3389/fearc.2025.1575572; (About DOIs).

Germania, creato il materiale impossibile per i chip del futuro

Germania, creato il materiale impossibile per i chip del futuro