Medieval poet Geoffrey Chaucer twice made references to an early work featuring a Germanic mythological character named Wade. Only three lines survive, discovered buried in a sermon by a late 19th century scholar. There has been much debate over how to translate those fragments ever since, and whether the long-lost work was a monster-filled epic or a chivalric romance. Two Cambridge University scholars now say those lines have been "radically misunderstood" for 130 years, supplying their own translation—and argument in favor of a romance—in a new paper published in the Review of English Studies.

We know such a medieval work once existed because it's referenced in other texts, most notably by Chaucer. He alludes to the "tale of Wade" in his epic poem Troilus and Criseyde and mentions "Wade's boat [boot]" in The Merchant's Tale—part of his masterpiece, The Canterbury Tales. A late 16th century editor of Chaucer's works, Thomas Speght, made a passing remark that Wade's boat was named "Guingelot," and that Wade's "strange exploits" were "long and fabulous," but didn't elaborate any further, no doubt assuming the tale was common knowledge and hence not worth retelling. Speght's truncated comment "has often been called the most exasperating note ever written on Chaucer," F.N. Robinson wrote in 1933.

So, the full story has been lost to history, although some remnant details have survived. For instance, there are mentions of Wade in an Old English poem, describing him as the son of a king and a "serpent-legged mermaid." The Poetic Edda mentions Wade's son, Wayland, as well as Wayland's brothers Egil and Slagfin. Wade is also briefly referenced in Malory's Morte D'Arthur and a handful of other texts from around the same period. Fun fact: J.R.R. Tolkien based his Middle-earth character Earendil on Wade; Earendil sails across the sky in a magical ship called Wingelot (or Vingilot).

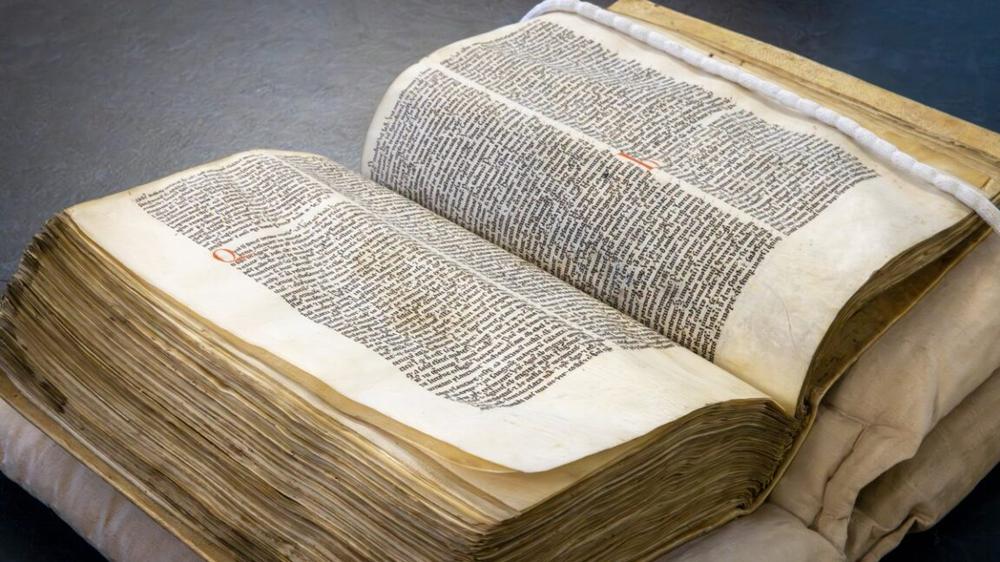

In 1896, Cambridge medievalist M.R. James was compiling a catalogue of medieval sermons and noted a passage of English verse in the otherwise Latin text of one such manuscript. (Life imitated art: James was also a writer and had just published a ghost story the year before about a Cambridge antiquarian who discovered a book of rare, long-lost medieval texts.)

He consulted a colleague, Israel Gollancz, who specialized in Middle English poetry for a translation: "Some are elves and some are adders; some are sprites that dwell by waters: there is no man, but Hildebrand only." (Folk legends refer to Hidebrande as a giant and Wade's father, who begat him on a mermaid.) So they concluded the lines were from a lost early 13th century romantic poem they called The Song of Wade. But like Speght before them, James and Gollancz offered no further comment.

A medieval meme

To Seb Falk and James Wade, authors of the new paper, it's clear that Wade was a well-known chivalric hero throughout the entire period of Middle English romance, and a likely folk hero. They think of Wade as a kind of medieval meme. "Romance writers invoke Wade as if he is meant to be recognizable as one of the greatest knights of chivalry," they wrote. The same appears to be true of the anonymous pastor who wrote the sermon containing the three-line fragment.

“The sermon itself is really interesting,” said Falk. “It’s a creative experiment at a critical moment when preachers were trying to make their sermons more accessible and captivating. Here we have a late-12th century sermon deploying a meme from the hit romantic story of the day. This is very early evidence of a preacher weaving pop culture into a sermon to keep his audience hooked. I once went to a wedding where the vicar, hoping to appeal to an audience who he figured didn’t often go to church, quoted the Black Eyed Peas’ song ‘Where is the Love?’ in an obvious attempt to seem cool. Our medieval preacher was trying something similar to grab attention and sound relevant.”

It's the translation of the word "elves" that is central to their new analysis. Based on their consideration of the lines in the context of the sermon (dubbed the Humiliamini sermon) as a whole, Falk and Wade believe the correct translation is "wolves." The confusion arose, they suggest, because of a scribe's error while transcribing the sermon: specifically, the letters "y" ("ylves") and "w" became muddled. The sermon focuses on humility, playing up how humans have been debased since Adam and comparing human behaviors to animals: the cunning deceit of the adder, for example, the pride of lions, the gluttony of pigs, or the plundering of wolves.

Falk and Wade think translating the word as "wolves" resolves some of the perplexity surrounding Chaucer's references to Wade. The relevant passage in Troilus and Criseyde concerns Pandarus, uncle to Criseyde, who invites his niece to dinner and regales her with songs and the "tale of Wade," in hopes of bringing the lovers together. A chivalric romance would serve this purpose better than a Germanic heroic epic evoking "the mythological sphere of giants and monsters," the authors argue.

The new translation makes more sense of the reference in The Merchant's Tale, too, in which an old knight argues for marrying a young woman rather than an older one because the latter are crafty and spin fables. The knight thus marries a much younger woman and ends up cuckolded. "The tale becomes, effectively, an origin myth for all women knowing 'so muchel craft on Wades boot,'" the authors wrote.

And while they acknowledge that the evidence is circumstantial, Falk and Wade think they've identified the author of the Humiliamini sermon: late medieval writer Alexander Neckam, or perhaps an acolyte imitating his arguments and writing style.

Review of English Studies, 2025. DOI: 10.1093/res/hgaf038 (About DOIs).

The Best PS5 Games

The Best PS5 Games