Mr. Scorsese debuts on Apple TV on October 17.

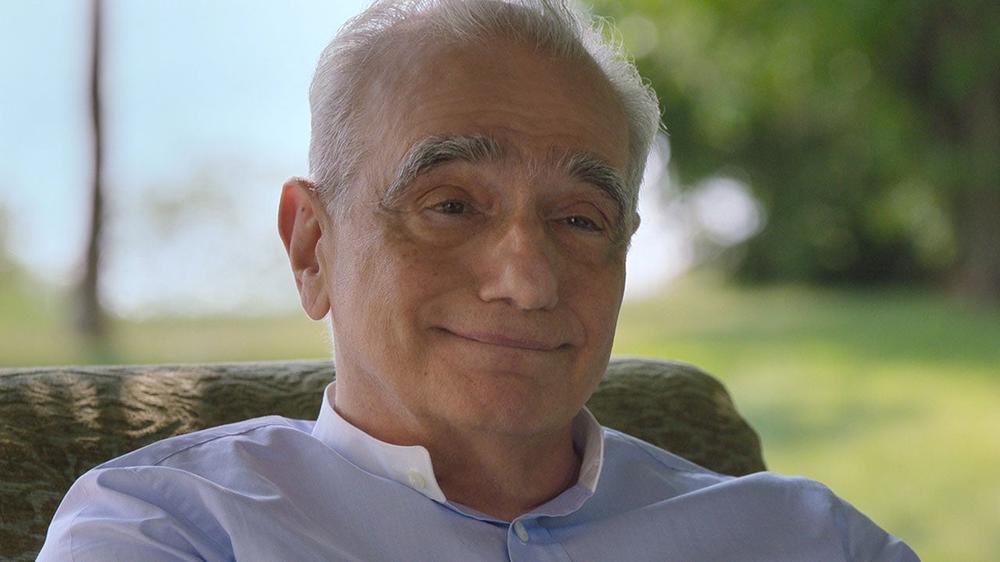

A five-part deep dive into one of our greatest living filmmakers, Mr. Scorsese is practically a semester of film school. Its subject, Goodfellas director Martin Scorsese, may as well be the series’ co-author; in Scorsese’s own words, “cinema is a matter of what’s in the frame,” and the documentary’s essayistic use of footage emanates from his rapid-fire recollections. The series flies out the gate with rabid energy, and while it eventually settles into something more traditional, it stands as a complete and coherent chronicle of one of Hollywood’s defining voices, in all his strengths and follies.

Helmed by The Ballad of Jack and Rose director Rebecca Miller, the show consists of five episodes, each about an hour in length, and each focusing on a specific era in Scorsese’s life and career. What’s more, unlike many modern docu-series that simply play like lengthy features, Mr. Scorsese is truly episodic in a way that not only makes each chapter satisfying, but provides hints of allure and excitement before the credits roll, enough to make you want to keep watching. These “cliffhangers” range from career highlights like Scorsese’s first meeting with Robert De Niro — his long-time friend and collaborator, with whom he first worked on Mean Streets — to moments of personal tumult, like the filmmaker’s late ‘70s drug addiction, which landed him in the hospital, and led to him bouncing back with the sports drama Raging Bull. No matter the nature of the story being told, the narrative always pivots around what movie Scorsese was making at the time, and why his images took the shape they did, or why he pulled from such specific sources of popular music, like The Rolling Stones.

The scene-to-scene structure is simple at the outset, with interview talking heads recounting Scorsese’s work, their encounters with him, and the nature of their collaboration. New filmmakers who admire him show as well — latter episodes frequently feature Ari Aster (Eddington) and Benny Safdie (The Smashing Machine) — but the real meat of the story comes courtesy of the people who knew Scorsese growing up, or during his early career — or at the very least, had similar upbringings. Goodfellas author and co-screenwriter Nicholas Pileggi is a key highlight, both for his insight into the criminal underworld that often influenced Scorsese, and for his own quips and anecdotes about the mafia.

Scorsese’s origins, from his immigrant family to his asthmatic childhood on the peripheries of the mob, make for fascinating insights into the director’s creative DNA. This is especially true when Miller and editor David Bartner parallel his stories with either footage of older classics that influenced Scorsese, or with recurring shots and themes from his work — like his numerous overhead, birds-eye-view establishing shots, which appear as the director recounts watching his neighborhood peers play from his bedroom window — firmly rooting his films in his experience.

As his career progresses, through films of violent obsession like Taxi Driver and The King of Comedy, a more political portrait fades into view. Along the way, Scorsese and his collaborators (like screenwriter Paul Schrader and editor Thelma Schoonmaker) are forced to confront a changing American landscape, and reckon with the inevitable criticisms their work would attract. The backlash to Scorsese’s inquiry into the human condition would come to a head during The Last Temptation of Christ, which even saw a theater in Paris being bombed.

Religion and human nature have long been of interest to Scorsese, and although the series picks apart how thoroughly he’s approached these themes, Mr. Scorsese isn’t a mere hagiography. Its subject has no doubt achieved mythical status in the modern movie landscape, but in keeping with Scorsese’s own approach to all things holy, Miller finds the deeply flawed, deeply human core at each stage of the filmmaker’s career, between the loved ones he ignored in pursuit of his passion and the blinders he would occasionally wear when directing women (an anecdote from Casino star Sharon Stone proves particularly cathartic).

It's an honest portrait of a man who’s lived a more interesting life than most audiences realize, and whose work has proved utterly fascinating throughout the decades. Some of the most fun and breezy moments come courtesy of New Hollywood peers like Brian DePalma and Steven Spielberg, and collaborators like Daniel Day-Lewis (Miller’s husband, who amusingly insists on calling the director “Martin” when everyone else refers to him as “Marty,” including his own parents). Other intimate recollections involve the kind of childhood stories from lifelong friends seldom found on DVD commentaries, and feel like a casual hangout, though they’re no less revelatory.

Miller, whose voice can be heard at times, asks questions that nudge her subjects into uncomfortable territory, about past tensions with Scorsese and where his own outbursts might have emanated from. Luckily, Scorsese himself doesn’t seem perturbed by these topics. He readily accepts that Miller’s project is, and ought to be, a broad, encompassing study, and the show is all the better for it.

“It’s just misogynistic”: Video comparing “girl dads” and “boy dads” has people pointing out how early gender bias starts

“It’s just misogynistic”: Video comparing “girl dads” and “boy dads” has people pointing out how early gender bias starts