Jay Kelly will be released in select theaters on November 14, and will debut on Netflix on December 5.

The cacophony of noises on the set of a major motion picture is enough to drive any person crazy. There’s yelling from all over, person after person after person trying to get someone’s attention, equipment moving and shifting under your (and everyone else’s) feet. But in director Noah Baumbach’s latest feature Jay Kelly, the title character couldn’t be more at home in the chaos. It’s what he, a generational superstar actor beloved for his work over the course of about 40 years, knows best. But what he finds as he approaches the twilight years of his storied career is that he maybe should’ve gotten to know other things better, namely his two daughters, who seem to be slipping through his fingers like grains of sand as they embark on their own lives.

This is, of course, the heart of this entertaining and poignant examination of the life of great artists – and Baumbach’s emotional resonance as a filmmaker and writer (a duty he shares this time with actress Emily Mortimer) allows him to explore it gently and graciously with nuance, frank comedy, and stark sentimentality in a way that feels truthful and human despite the larger-than-life nature of the film’s subject. Oh, and on that note I should mention: Kelly is played by none other than George Clooney.

Clooney is the heart and soul of this film, not only because he’s an excellent actor who’s proven himself as such over the years, but because he innately understands what Jay Kelly is going through as a person. He’s lived that life, the life of someone who knows a thing or two about the personal sacrifices necessary in the face of great art. Jay Kelly is, ultimately, an obvious stand-in for Clooney himself, but that’s why the character, and the film overall, works. It’s a necessary element of Baumbach’s picture, especially considering the narrative is somewhat less personal to the director than many of his other works. Clooney’s personal connection to the narrative acts as somewhat of a surrogate for the connection Baumbach (Kicking and Screaming, The Squid and the Whale, Marriage Story) always has to his stories, imbuing it with the same kind of life his other somewhat autobiographical projects have had in the past. It’s key, because without that kind of smart casting, this film probably would fall way more flat than it does. Kelly, as a product of Baumbach’s direction and writing and Clooney’s choices and instincts, is a beautiful disaster of a man, one who is noble in his trying and human in his errors. He is, ultimately, just like any of us who try and try and try: We’re bound to make mistakes along the way.

Kelly is, of course, nothing without the people who helped him throughout his career, the ones who ended up being a surrogate for the family he neglected. That’s where Adam Sandler comes in with an excellent turn as Kelly’s manager Ron, who has been with him for his entire 40-year career. Sandler is of course known for his comedic chops, but has played straight dramatic roles over the years as well, including in 2019’s Uncut Gems. Here his Ron is touching, drenched in charm and sadness in equal measure.

The supporting cast in general – namely Kelly’s team, made up of Sandler and Laura Dern as his publicist, as well as Greta Gerwig as Ron’s wife, Grace Edwards and Riley Keough as Kelly’s somewhat estranged daughters, and an exciting Billy Crudup as an old friend who resurfaces in a movie-stealing scene — brings the entire picture together in the same way an artist's team brings together all the challenging elements of their extravagant and hectic lives so they can just be who the world wants them to be. Dern is hilarious as she lays out some heartfelt truths worth examining about who your friends are in this business. Gerwig also adds a great bit of comedic relief to the project alongside Sandler’s real-life daughters and the young actor who splits sides as Ron’s son.

Edwards and Keough are playing very different women with different goals and ideals, but they each bring a sense of independence and self-preservation to the roles that makes the crucial nature of their characters stand out. They’re both a joy to watch, though their ultimate paths are somewhat tragic for Kelly because he’s missed his opportunity to ride alongside them. Both performers embody that tragedy in their own ways, with Edwards’ quirky, free-spirited, and headstrong soul bare throughout her time in the narrative and Keough’s resentment and anger bubbling over with just the right amount of tension and consideration. As for Crudup, he’s the one-two punch (no pun intended – if you know you know) of the film and his turn, though short, is revelatory for the same reasons Kelly praises him in the film: his ability to perform in every sense of the concept, and to breathe life and truth into every word, biting or tender. These performances are the bedrock of Clooney’s ability to build a full life around Kelly.

Visually, Baumbach is also doing quite a bit of exploring. His surreal approach to embodying Kelly’s mind, and by extension his regrets, is fun and compelling to see. It truly feels as though he is walking through his own mind as he makes his way through every day, unable to help but remember the moments that have defined him and his life over the years. Baumbach has Kelly do this in the literal sense, as one doorway in one locale in the present leads to landscapes of haunting memory in the past. It’s an effective way for Kelly to explore his emotional life, his mortality, and his accomplishments and failures professional and personal – and how they have ultimately affected who he was, who he is, and who he will be throughout the remainder of his career and life.

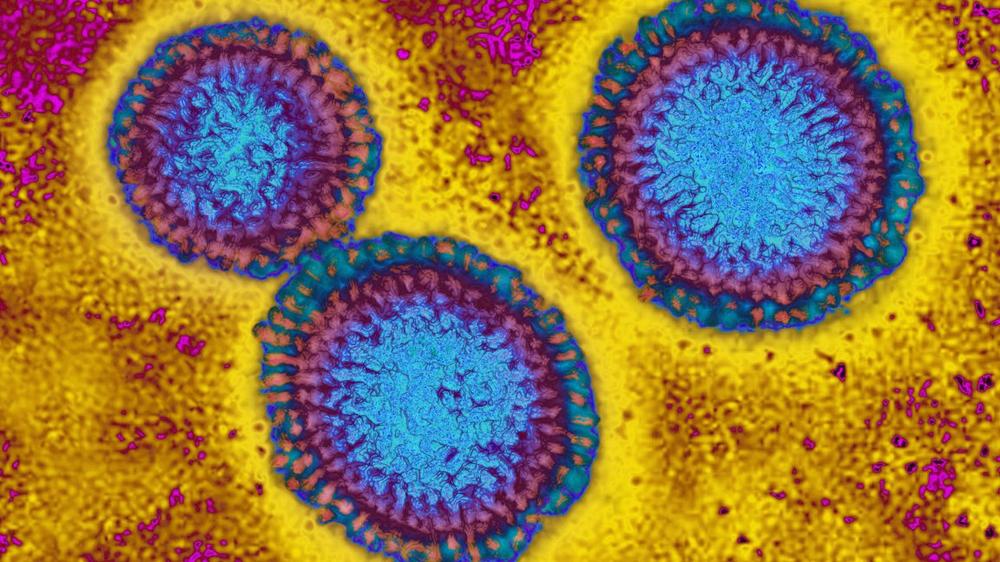

This flu season looks grim as H3N2 emerges with mutations

This flu season looks grim as H3N2 emerges with mutations