As U.S.-led efforts to end Russia's war against Ukraine were gaining momentum, Poland, once among Kyiv's most vocal backers, was noticeably absent from high-level talks, sparking debate over its diminished role.

The country, which provided an estimated 4.5 billion euros ($5.2 billion) in military aid since 2022 and hosts the critical Rzeszow-Jasionka hub for Western weapons deliveries, has struggled to maintain its early prominence.

Analysts say dwindling military stockpiles and shifting domestic politics have reduced its role.

"Poland's foreign policy is used for domestic political purposes, meaning it is, in a certain sense, subordinated to them," Michal Lebduska, an analyst at the Association for International Affairs (AMO), told the Kyiv Independent.

"This creates a whole set of problems, and from this set of problems comes the fact that Poland is no longer as reliable and important a partner for Ukraine as it once was."

Domestic pressures

During the first year of the all-out war, Poland had resources it could offer to help Ukraine, and at that time, its support seemed stronger than that of many other countries.

"There was a lot of old Soviet equipment, some tanks, and other machinery," Lebduska said, noting that this allowed Warsaw to respond quickly when the war began. "But now the problem is that, first of all, Poland no longer has the same resources it once did."

Over time, internal politics have also reshaped Warsaw's approach.

Far-right parties, such as Poland's Confederation, have gained traction by portraying aid to Kyiv as a costly burden and framing military assistance as largely unreciprocated.

A June IBRiS poll showed 46% of Poles now support reducing or ending military aid, compared to 26% who opposed assistance in February 2024. The rhetoric has fueled fatigue and skepticism, even as Russia's war continues into its fourth year.

The June 1 election of right-wing nationalist Karol Nawrocki as president deepened uncertainty. While Nawrocki condemns Russia's aggression, he opposes Ukraine's NATO and EU accession and has accused Kyiv of exploiting its allies.

"The problem is, we still don't know what Nawrocki's policy toward Ukraine will look like," Polish political scientist Pawel Borkowski said. "From the campaign and from his close ties to the Confederation party, there are suspicions he may take a less pro-Ukrainian stance."

Absence in Washington

That ambiguity was underscored when Poland was missing from the Aug. 18 talks in Washington.

A number of European leaders joined President Volodymyr Zelensky in their meeting with U.S. President Donald Trump, following his summit with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Alaska.

Nawrocki's absence sparked criticism at home.

"Apparently, neither the U.S. nor Ukraine saw any reason to talk to us. Despite our enormous assistance (to Kyiv) and our geographical location, we count for less than Finland. It's just sad," Confederation leader Slawomir Mentzen wrote on X.

Nawrocki defended Poland's absence on Aug. 18, saying he had already discussed the country's position with Trump and European leaders earlier in the week.

He said that within the "Coalition of the Willing," which consists of 33 states pledging security guarantees to Ukraine, Poland was represented by its government, not the presidency.

The government said Prime Minister Donald Tusk did not attend because the meeting followed the same format as previous talks among European leaders that included Trump.

"At that time, Poland was represented by President Karol Nawrocki," spokesperson Adam Szlapka said.

Poor relations between Trump and Tusk, who indirectly supported Democratic candidate Kamala Harris during the U.S. election campaign, help explain Warsaw's exclusion, Aleksandra Kusztal, a political scientist at the Jan Kochanowski University of Kielce, said.

"These relations are bad. There is no element of so-called good chemistry between the two gentlemen (Trump and Tusk)," she told the Kyiv Independent.

Lebduska said that both Tusk's government and the new president, Nawrocki, face challenges that constrain their ability to act effectively in international diplomacy.

"On one hand, Tusk's government is not a strong partner for Trump and the current U.S. administration," he said. "On the other hand, Nawrocki, with his anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western rhetoric, is also not a partner for Europeans."

"They have ended up in a trap: first, because of internal disputes, and second, because they were unable to effectively represent Poland at their levels."

No Polish peacekeepers

As discussions among Kyiv's European allies shifted to potential peacekeeping missions that could follow a possible ceasefire, Poland ruled out sending troops.

"We will not send Polish soldiers to Ukraine. This is the government's position not for a week, but for many months," Defense Minister Wladyslaw Kosiniak-Kamysz said on Aug. 20.

The statement came as Bloomberg reported on Aug. 19 that European officials have discussed sending British and French troops to Ukraine, along with contingents from roughly 10 other countries.

Analysts say Poland's cautious stance reflects longstanding speculation. Both the Law and Justice (PiS) party and the Confederation signaled during the campaign that they opposed committing Polish forces directly to Ukraine.

"During the presidential campaign, there were very strong statements that the Polish government would send Polish soldiers to Ukraine, which is not acceptable," Kusztal noted.

She said that Tusk's government is reacting in a way meant to give the public the sense that deploying Polish troops to Ukraine is impossible.

"I also think this could be one reason why Poland is not seen as a key player in the broader peacemaking discussions," she added.

Drone incident highlights vulnerability

Warsaw's stance faced renewed scrutiny on Aug. 20, when a Russian drone crashed in a rural area of Poland's Lublin region near the Ukrainian border.

Officials described it as a deliberate provocation, with Foreign Minister Radoslaw Sikorski pledging a diplomatic protest.

Yet the government's cautious response was widely perceived as weak. Analysts suggested Warsaw avoided escalating rhetoric to prevent stoking fear at home.

"A reaction like 'oh my God, we were attacked, what should we do next?' would be a really bad idea, as it could create unnecessary social panic," Kusztal said.

Borkowski noted that liberals across Poland generally see fear as already deeply embedded in society through political messaging and past election campaigns.

Adding further tension would only serve the far right, he said.

From big to small

Poland's absence in Washington and its restrained stance reflect a broader shift.

Once a driving force behind Europe's support for Ukraine, Warsaw's influence appears reduced by internal disputes, limited resources, and strained ties with key partners.

"The question now is whether Poland can truly be a major player. I highly doubt it — first because of internal disputes between the government and the opposition, which weaken Poland on the international stage," Lebduska said.

"And also because Poland doesn't have much to offer Ukraine at the moment, it ends up being a much weaker player than it could have been."

Note from the Author

Hi, this is Tim. The author of this article. Thank you for taking the time to read it.

At the Kyiv Independent, we speak to top experts to bring you accurate, in-depth reporting. We don't have a wealthy owner or political backing. We rely on readers like you to support our work.

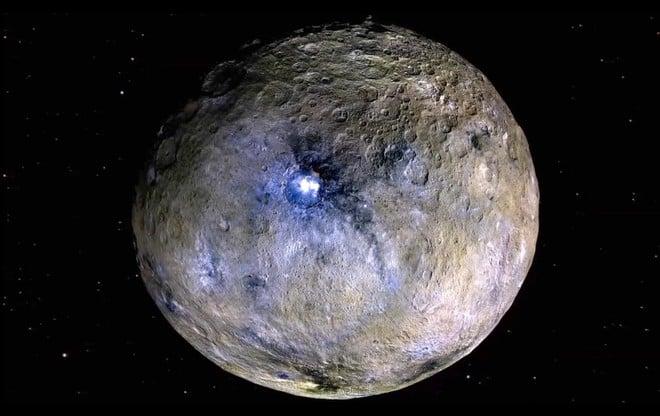

Scoperta NASA: il pianeta nano Cerere poteva ospitare vita microbica

Scoperta NASA: il pianeta nano Cerere poteva ospitare vita microbica