Researchers recently reported encountering a phishing attack in the wild that bypasses a multifactor authentication scheme based on FIDO (Fast Identity Online), the industry-wide standard being adopted by thousands of sites and enterprises.

If true, the attack, reported in a blog post Thursday by security firm Expel, would be huge news, since FIDO is widely regarded as being immune to credential phishing attacks. After analyzing the Expel write-up, I’m confident that the attack doesn’t bypass FIDO protections, at least not in the sense that the word “bypass” is commonly used in security circles. Rather, the attack downgrades the MFA process to a weaker, non-FIDO-based process. As such, the attack is better described as a FIDO downgrade attack. More about that shortly. For now, let’s describe what Expel researchers reported.

Abusing cross-device sign-ins

Expel said the “novel attack technique” begins with an email that links to a fake login page from Okta, a widely used authentication provider. It prompts visitors to enter their valid user name and password. People who take the bait have now helped the attack group, which Expel said is named PoisonSeed, clear the first big hurdle in gaining unauthorized access to the Okta account.

The FIDO spec was designed to mitigate precisely these sorts of scenarios by requiring users to provide an additional factor of authentication in the form of a security key, which can be a passkey, or physical security key such as a smartphone or dedicated device such as a Yubikey. For this additional step, the passkey must use a unique cryptographic key embedded into the device to sign a challenge that the site (Okta, in this case) sends to the browser logging in.

One of the ways a user can provide this additional factor is by using a cross-device sign-in feature. In the event there is no passkey on the device being used to log in, a user can use a passkey for that site that’s already resident on a different device, which in most cases will be a phone. In these cases, the site being logged into will display a QR code. The user then scans the QR code with the phone, and the normal FIDO MFA process proceeds as normal.

Expel said that PoisonSeed has found a clever sleight of hand to bypass this crucial step. As the user enters the username and password into the fake Okta site, a PoisonSeed team member enters them in real time into a real Okta login page. As Thursday’s post went on to explain:

In the case of this attack, the bad actors have entered the correct username and password and requested cross-device sign-in. The login portal displays a QR code, which the phishing site immediately captures and relays back to the user on the fake site. The user scans it with their MFA authenticator, the login portal and the MFA authenticator communicate, and the attackers are in.

This process—while seemingly complicated—effectively bypasses any protections that a FIDO key grants, and gives the attackers access to the compromised user’s account, including access to any applications, sensitive documents, and tools such access provides.

How FIDO makes such attacks impossible

The end result, the security firm said, was an adversary-in-the-middle attack that tampered with the QR code process to bypass FIDO MFA. As noted earlier, writers of the FIDO spec anticipated such attack techniques and built defenses that make them impossible, at least in the form described by Expel. Had the targeted Okta MFA process followed FIDO requirements, the login would have failed for at least two reasons.

First, the device providing the hybrid form of authentication would have to be physically close enough to the attacker device logging in for the two to connect over Bluetooth. Contrary to what Expel said, this is not an “an additional security feature.” It’s mandatory. Without it, the authentication will fail.

Second, the challenge the hybrid device would have to sign would be bound to the domain of the fake site (here okta[.]login-request[.]com) and not the genuine Okta.com domain. Even if the hybrid device was in close proximity to the attacker device, the authentication would still fail, since the URLs don’t match.

What Expel seems to have encountered is an attack that downgraded FIDO MFA with some weaker MFA form. Very likely, this weaker authentication was similar to those used to log in to a Netflix or YouTube account on a TV with a phone. Assuming this was the case, the person who administered the organization’s Okta login page would have had to deliberately choose to allow this fallback to a weaker form of MFA. As such, the attack is more accurately classified as a FIDO downgrade attack, not a bypass.

An Expel representative agreed, writing: “You're spot on with identifying that we invoked a specific meaning within the authentication security space and did not intend to do so. This is not a FIDO key bypass attack. This is a downgrade attack, as you correctly note.” The representative said Expel is in the process of updating the post.

To steer clear of such attacks, admins should think long and hard before allowing their FIDO-protected authentication processes to fall back to other forms. Relying solely on FIDO can be risky since, at this point in the FIDO evolution, it’s still impractical to manage and export passkeys in the same way as passwords and other forms of credentials. End users should take pains to use only FIDO-compliant forms of authentication, although the distinction between the two in the attack Expel described may not be easy for some.

In the meantime, people relying on passkeys should carry on.

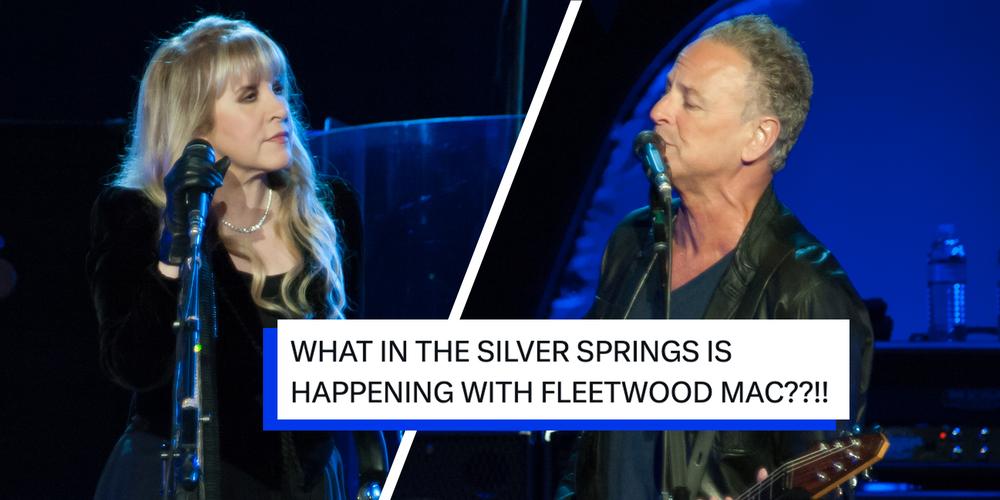

“Those two crazy kids”: Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham divide fans after posting project teaser to social media

“Those two crazy kids”: Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham divide fans after posting project teaser to social media