Back in 2023, we reported on MIT scientists’ conclusion that the ancient Romans employed “hot mixing” with quicklime, among other strategies, to make their famous concrete, giving the material self-healing functionality. The only snag was that this didn’t match the recipe as described in historical texts. Now the same team is back with a fresh analysis of samples collected from a recently discovered site that confirms the Romans did indeed use hot mixing, according to a new paper published in the journal Nature Communications.

As we’ve reported previously, like today’s Portland cement (a basic ingredient of modern concrete), ancient Roman concrete was basically a mix of a semi-liquid mortar and aggregate. Portland cement is typically made by heating limestone and clay (as well as sandstone, ash, chalk, and iron) in a kiln. The resulting clinker is then ground into a fine powder with just a touch of added gypsum to achieve a smooth, flat surface. But the aggregate used to make Roman concrete was made up of fist-sized pieces of stone or bricks.

In his treatise De architectura (circa 30 CE), the Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius wrote about how to build concrete walls for funerary structures that could endure for a long time without falling into ruin. He recommended the walls be at least two feet thick, made of either “squared red stone or of brick or lava laid in courses.” The brick or volcanic rock aggregate should be bound with mortar composed of hydrated lime and porous fragments of glass and crystals from volcanic eruptions (known as volcanic tephra).

Admir Masic, an environmental engineer at MIT, has studied ancient Roman concrete for several years. For instance, in 2019, Masic helped pioneer a new set of tools for analyzing Roman concrete samples from Privernum at multiple length scales—notably, Raman spectroscopy for chemical profiling and multi-detector energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) for phase mapping the material. Masic was also a co-author of a 2021 study analyzing samples of the ancient concrete used to build a 2,000-year-old mausoleum along the Appian Way in Rome known as the Tomb of Caecilia Metella, a noblewoman who lived in the first century CE.

And in 2023, Masic’s group analyzed samples taken from the concrete walls of the Privernum, focusing on strange white mineral chunks known as “lime clasts,” which others had largely dismissed as resulting from subpar raw materials or poor mixing. Masic et al. concluded that was not the case. Rather, the Romans deliberately employed “hot mixing” with quicklime that gave the material self-healing functionality. When cracks begin to form in the concrete, they are more likely to move through the lime clasts. The clasts can then react with water, producing a solution saturated with calcium. That solution can either recrystallize as calcium carbonate to fill the cracks or react with the pozzolanic components to strengthen the composite material.

Under construction

However, the concrete recipe described by Vitruvius did not match the hot mixing process. “Having a lot of respect for Vitruvius, it was difficult to suggest that his description may be inaccurate,” Masic said. “The writings of Vitruvius played a critical role in stimulating my interest in ancient Roman architecture, and the results from my research contradicted these important historical texts.”

Then archaeologists discovered the remains of what was once an active construction site in Pompeii, with tools and piles of raw materials scattered about, a half-built wall, completed buttresses, and even mortar repairs to an existing wall. Masic described it as a veritable “time capsule” holding even more secrets about how the Romans made their concrete.

Masic et al.’s latest isotopic analysis of samples taken from the site confirms that the concrete had the same lime clasts as those used to build Privernum. Intact quicklime fragments showed they had been premixed with other dry raw materials—a crucial early step in a hot mixing process. Furthermore, the volcanic ash used in the cement contained pumice, and those pumice particles would chemically react with the surrounding solution over time to create new, strengthening mineral deposits. As for Vitruvius, Masic suggests that the historian may have been misinterpreted, pointing to a passing mention of latent heat during the cement mixing process that might indicate hot mixing.

Masic is confident enough in these results that he founded a new manufacturing company drawing on the lessons he’s learned over the last 10 years to make more durable modern concrete. “This material can heal itself over thousands of years, it is reactive, and it is highly dynamic,” said Masic. “It has survived earthquakes and volcanoes. It has endured under the sea and survived degradation from the elements. We don’t want to completely copy Roman concrete today. We just want to translate a few sentences from this book of knowledge into our modern construction practices.”

DOI: Nature Communications, 2025. 10.1038/s41467-025-66634-7 (About DOIs).

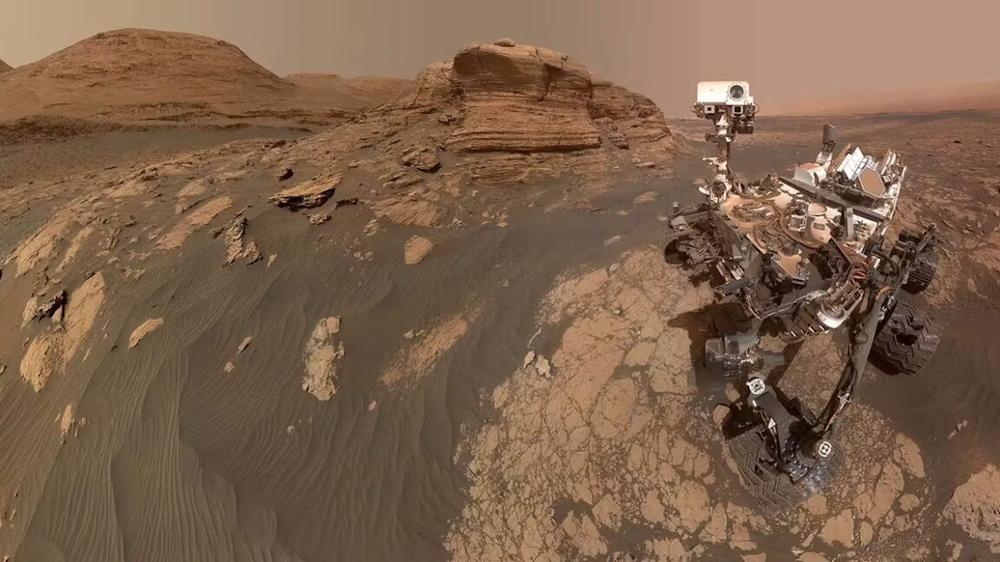

In a major new report, scientists build rationale for sending astronauts to Mars

In a major new report, scientists build rationale for sending astronauts to Mars