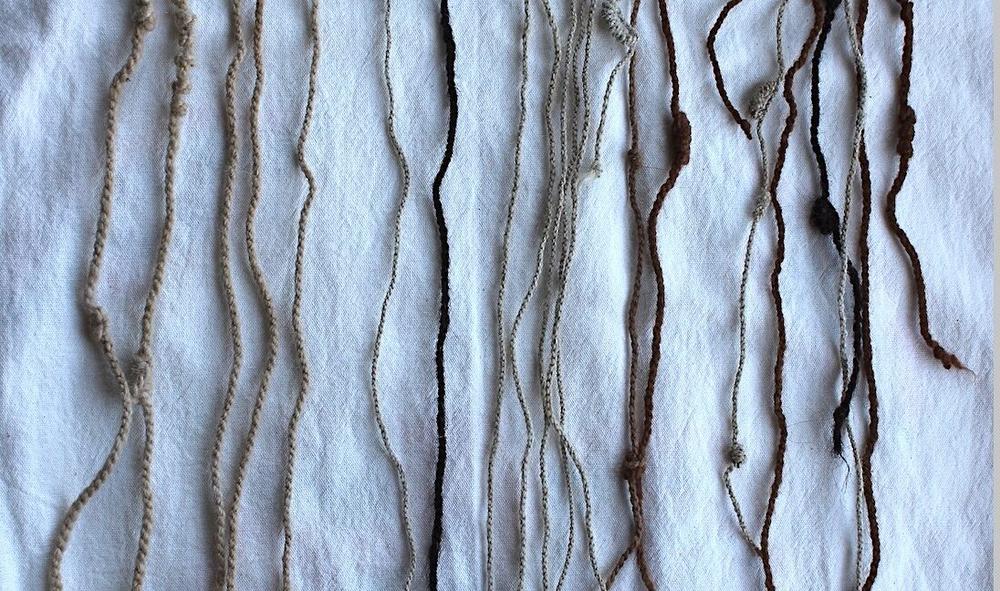

Inca bureaucrats recorded all the goings-on in their bustling empire using knotted cords called khipu, where the position and order of the knots represented numbers. They relied on the khipu system to track people, taxes, produce, livestock, and products like woven cloth and beer.

Because khipu were so vital to the Inca government, and because the khipu itself is such a sophisticated way of recording numbers, colonial writers decided that these tools must be the exclusive knowledge of a very specialized, elite class of bureaucrats. But a recent study, analyzing hair from a khipu made around 1498 CE, suggests that even common folk had a good grasp of this intricate way of recording numbers.

A lasting signature on a gorgeous piece of work

University of St. Andrews archaeologist Sabine Hyland and her colleagues recently analyzed a stand of hair from a 500-year-old khipu—one they expected to be the handiwork of an especially high-ranking member of the Inca empire, based on how beautifully it was crafted.

“It’s very fine and has subtle embellishments, like decorative braiding on the ends of some pendants. I wondered if this was from a very high-status person indeed,” Hyland told Ars. “It was [a] surprise when we got the results back, and it showed that this person had the diet of a commoner.”

The threads that made up the khipu’s knotted strands had come from a camelid (probably an alpaca or llama), but those strands hung from a cord of human hair: a 104 centimeter-long set of locks, folded in half and twisted into a sturdy cord. Almost certainly, the person who made the khipu intended their hair to serve as a deeply personal signature for their work. For the Inca, hair contained a person’s spiritual essence; it also happens to contain a chemical record that can shed light on what they ate and where they lived.

Ratios of certain chemical isotopes in the khipu-maker’s hair suggest that they are a diet of primarily tubers and legumes, with no seafood and very little meat at the rocks and soil where all that food grew.

In other words, the khipu-maker’s hair was a signature in a very tangible way as well as a symbolic one. And the information in that signature could challenge some of what we thought about Inca society and the vibrant threads that link Inca and their modern descendants. It may even hint at the role of women in spreading this very technical knowledge to far-flung Inca villages.

Numbers: Not just for imperial bureaucrats

Colonial documents describe how each community in the Inca Empire supported two high-ranking khipu experts who kept accounts of local population, labor, and tax records. These officials apparently got some cushy benefits, including “a very good allotment of all sorts of sustenance for each month of the year.”

The official khipu experts would have been born to blue-blooded families and raised for positions of importance. Obviously, mere women and peasants could never... except that recently unearthed evidence is showing that they could and did.

At one Inca cemetery in Peru, archaeologists unearthed the remains of a woman buried with her khipu. And now Hyland and her colleagues’ recent study of the 500-year-old khipu (officially labelled KH0631) shows that an Inca commoner not only made a khipu but a finely-crafted, beautifully decorated one at that. And it apparently had nothing to do with the business of running an empire.

“We don’t know what KH0631 recorded,” Hyland told Ars. But because this person was not a high-ranking bureaucrat, she said the khipu probably didn’t contain official business. “I suspect it was something more personal—perhaps encoding the offerings that the person made at different ritual places in the landscape.”

Women in STEM: Inca Edition

In the late 1500s, a few decades after the khipu in this recent study was made, an Indigenous chronicler named Guaman Poma de Ayala described how older women used khipu to “keep track of everything” in aqllawasai: places that basically functioned as finishing schools for Inca girls. Teenage girls, chosen by local nobles, were sent away to live in seclusion at the aqllawasai to weave cloth, brew chicha, and prepare food for ritual feasts.

What happened to the girls after aqllawasai graduation was a mixed bag. Some of them were married (or given as concubines) to Inca nobles, others became priestesses, and some ended up as human sacrifices. But some of them actually got to go home again, and they probably took their knowledge of khipu with them.

“I think this is the likely way in which khipu literacy made it into the countryside and the villages,” said Hyland. “These women, who were not necessarily elite, taught it to their children, etc.” That may be where the maker of KH0631 learned their skills: either in an aqllawasai or from a graduate of one (we still don’t know this particular khipu-maker’s gender).

“Science confirming what they already knew”

The finely crafted khipu turning out to be the work of a commoner shows that numeracy was widespread and surprisingly egalitarian in the Inca empire, but it also reveals a centuries-long thread connecting the Inca and their descendants.

Modern people—the descendants of the Inca—still use khipu today in some parts of Peru and Chile. Some scholars (mostly non-Indigenous ones) have argued that these modern khipu weren’t really based on knowledge passed down for centuries but were instead just a clumsy attempt to copy the Inca technology. But if commoners were using khipu in the Inca empire, it makes sense for that knowledge to have been passed down to modern villagers.

“It points to a continuity between Inka and modern khipus,” said Hyland. “In the few modern villages with living khipu traditions, they already believe in this continuity, so it would be the case of science confirming what they already know.”

Science Advances, 2025. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adv1950 (About DOIs).

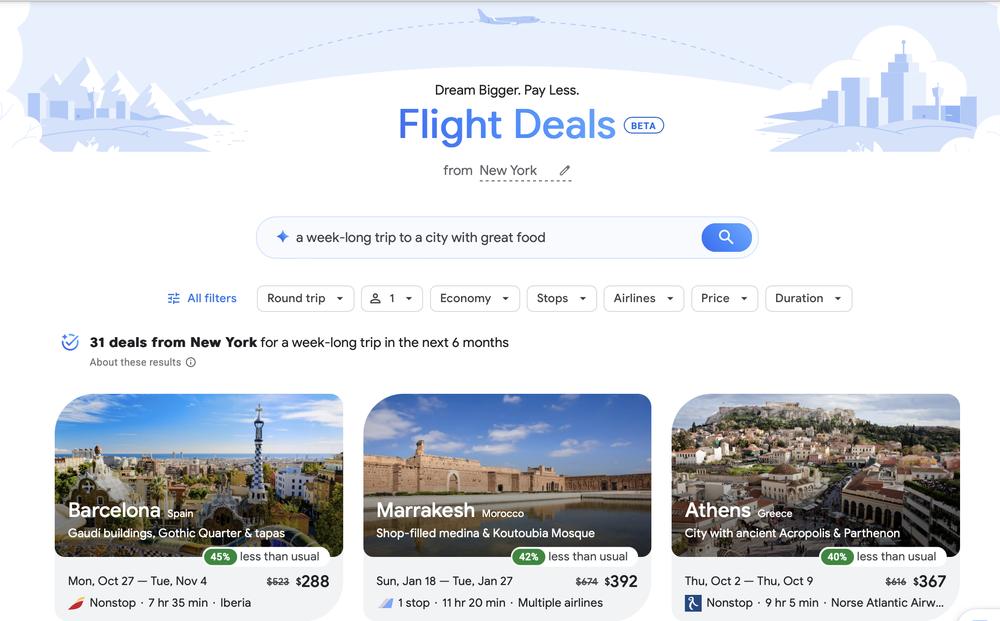

Google Flights can help you book a trip when you don’t know where to go

Google Flights can help you book a trip when you don’t know where to go