It's easier than ever to manipulate video footage to deceive the viewer and increasingly difficult for fact checkers to detect such manipulations. Cornell University scientists developed a new weapon in this ongoing arms race: software that codes a "watermark" into light fluctuations, which in turn can reveal when the footage has been tampered with. The researchers presented the breakthrough over the weekend at SIGGRAPH 2025 in Vancouver, British Columbia, and published a scientific paper in June in the journal ACM Transactions on Graphics.

“Video used to be treated as a source of truth, but that’s no longer an assumption we can make,” said co-author Abe Davis, of Cornell University, who first conceived of the idea. “Now you can pretty much create video of whatever you want. That can be fun, but also problematic, because it’s only getting harder to tell what’s real.”

Per the authors, those seeking to deceive with video fakes have a fundamental advantage: equal access to authentic video footage, as well as the ready availability of advanced low-cost editing tools that can learn quickly from massive amounts of data, rendering the fakes nearly indistinguishable from authentic video. Thus far, progress on that front has outpaced the development of new forensic techniques designed to combat the problem. One key feature is information asymmetry: an effective forensic technique must have information not available to the fakers that cannot be learned from publicly available training data.

Granted, digital watermarking techniques do exist that make good use of information asymmetry, but the authors note that most of those tools fall short on other desired attributes. Other methods may require control over the recording camera or access to the original unmanipulated video. And while a checksum, for example, can determine if a video file has been changed, it can't tell the difference between standard video compression or something malicious, like inserting virtual objects.

Hiding in the light

Previously, the Cornell team had figured out how to make small changes to specific pixels to tell if a video had been manipulated or created by AI. But its success depended on the creator of the video using a specific camera or AI model. Their new method, "noise-coded illumination" (NCI), addresses those and other shortcomings by hiding watermarks in the apparent noise of light sources. A small piece of software can do this for computer screens and certain types of room lighting, while off-the-shelf lamps can be coded via a small attached computer chip.

“Each watermark carries a low-fidelity time-stamped version of the unmanipulated video under slightly different lighting. We call these code videos,” Davis said. “When someone manipulates a video, the manipulated parts start to contradict what we see in these code videos, which lets us see where changes were made. And if someone tries to generate fake video with AI, the resulting code videos just look like random variations.” Because the watermark is designed to look like noise, it's difficult to detect without knowing the secret code.

The Cornell team tested their method with a broad range of types of manipulation: changing warp cuts, speed and acceleration, for instance, and compositing and deep fakes. Their technique proved robust to things like signal levels below human perception; subject and camera motion; camera flash; human subjects with different skin tones; different levels of video compression; and indoor and outdoor settings.

“Even if an adversary knows the technique is being used and somehow figures out the codes, their job is still a lot harder,” Davis said. “Instead of faking the light for just one video, they have to fake each code video separately, and all those fakes have to agree with each other.” That said, Davis added, “This is an important ongoing problem. It’s not going to go away, and in fact it's only going to get harder,” he added.

DOI: ACM Transactions on Graphics, 2025. 10.1145/3742892 (About DOIs).

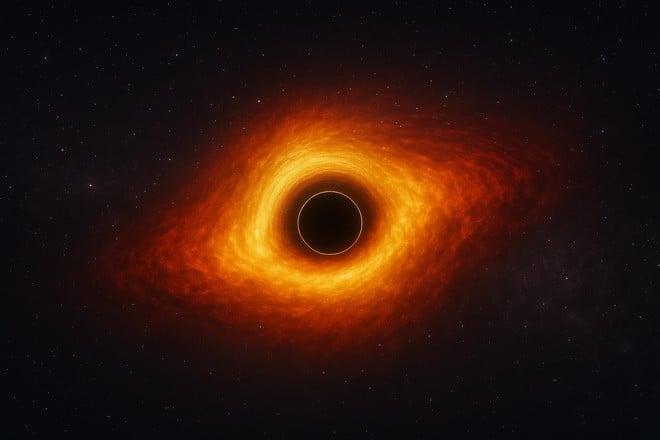

Scoperto il buco nero più antico mai osservato: nato 500 milioni di anni dopo il Big Bang

Scoperto il buco nero più antico mai osservato: nato 500 milioni di anni dopo il Big Bang