Two chunks of ocher unearthed at ancient rock shelters in Ukraine were actually Neanderthal crayons, according to a recent study. The pair of artifacts, unearthed from layers 47,000 and 46,000 years old, showed signs of being deliberately shaped into crayons and resharpened over time. A third piece of ocher had been carefully carved with parallel lines. The finds add to the growing body of evidence that Neanderthals had an artistic streak.

Please pass Og the yellow crayon

Rock shelters, occupied by Neanderthals between 100,000 and 33,000 years ago, dot the landscape near the modern city of Bilohirsk in Crimea (a peninsula in southern Ukraine). Archaeologists studying those rock shelters have unearthed dozens of chunks of an iron-rich mineral called ocher. Many of them have flakes knocked out or grooves gouged into their surface, which mark how Neanderthals extracted powdery red, orange, or yellow pigment from the stone. D’Errico and his colleagues used X-ray fluorescence and scanning electron microscopes to examine 16 ocher chunks to better understand exactly what ancient Crimean Neanderthals were doing with the stuff.

Most of those ocher chunks could have been used for nearly anything. Ocher is handy not just as a pigment but also for tanning animal hides, mixing with resins into adhesives for hafting tools, or even repelling insects and preventing infection. Knapping a few flakes off a hard nodule of ocher, then crushing them into powder (or just carving out a chunk of a softer, more crumbly piece), is a good way to prepare it for any of those uses. But two pieces, both from a site called Zaskalnaya V, were clearly different.

“One is shaped into a crayon-like tool, with repeated resharpening,” wrote D’Errico and his colleagues in their recent paper. “Another appears to be a crayon fragment.”

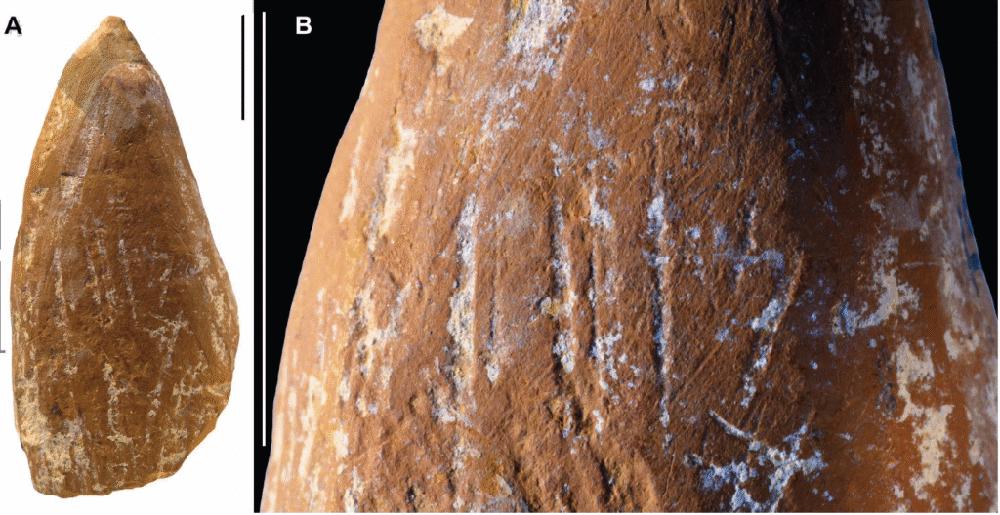

One, a 44.8-millimeter-long, 23.3-millimeter-wide chunk of yellow ocher, showed the telltale marks of having been roughly scraped into a pointed shape, then sanded smooth on a grindstone. Chisel marks near the tip even “suggest use or intentional sharpening to maintain its point,” as D’Errico and his colleagues put it. But like a lot of crayons today, this one was eventually blunted by rough use and eventually lost amid the debris on the rock shelter floor. A second artifact—this one a 25.4-millimeter-long chunk of red ocher—looks much like the yellow one, except that its tip has been broken off.

“The combination of shaping, wear, and resharpening indicates they were used to draw or mark on soft surfaces,” D’Errico told Ars in an email. “Although the material is too fragile to reveal the specific material on which they were used, such as hide, human skin, or stone, an experimental approach may, in the future, allow us at least to rule out their use on some materials.”

A 73,000-year-old drawing from Blombo Cave in South Africa looks like it was made with tools much like the ocher crayons from Crimea, which means that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens both invented crayons in their own little corners of the world at around the same time.

Sometimes you’re the crayon, sometimes you’re the canvas

A third item from Zaskalnaya V is a flat piece of orange ocher. One side is covered with a thin layer of hard, dark rock. But more than 47,000 years ago, someone carefully cut several deep lines, regularly spaced and almost parallel, into its surface. The area of stone between the lines has been worn and polished smooth, suggesting that someone carried it and handled it for years.

“The polish smoothing the engraved lines suggest that the piece was curated, perhaps transported in a bag,” D’Errico told Ars. Whoever carved the lines into the piece of ocher also appears to have been right-handed, based on the angle of the incisions’ walls.

The finds join a host of other evidence of Neanderthal artwork and jewelry, from 57,000-year-old finger marks on a cave wall in France to 114,000-year-old ocher-painted shells in Spain.

“Traditionally viewed as lacking the cognitive flexibility and symbolic capacity of humans, the Neanderthals of Crimea demonstrate the opposite: They engaged in cultural practices that were not merely adaptive but deeply meaningful,” wrote D’Errico and his colleagues. “Their sophisticated use of ocher is one facet of their complex cultural life.”

Coloring in some details of Neanderthal culture

It’s hard to say whether the rest of the ocher from the Zaskalnaya sites and other nearby rock shelters meant anything to the Neanderthals beyond the purely pragmatic. However, it’s unlikely that humans (of any stripe) could spend 70,000 years working with vividly colored pigment without developing a sense of aesthetics, assigning some meaning to the colors, or maybe doing both.

“Other authors point out that symbolic and utilitarian functions are intimately linked among traditional populations,” wrote D’Errico and his colleagues, “and that, as a result, it would have been difficult for a systematic use of ocher powders to exist over a long period of time without a symbolic dimension being rather quickly attached to it.”

Tens of thousands of years later, without direct evidence, all we can do is speculate. Which, to be fair, is tremendously interesting as long as it comes with the right caveats and understanding of its limitations. But there are a growing number of places and times where we do have direct evidence that Neanderthals were using color to signal something meaningful to each other, even if we don’t know whether the meaning was “Og is the deputy chief of all the people east of the river,” “Zogg belongs to the people who live in this valley, not that one,” or “Grogg really likes yellow.”

As D’Errico and his colleagues point out, that meaning probably varied from place to place, just as it does today. In most of Europe, white is the traditional color for a wedding, but in China, white is for funerals. Millennial gray is in its heyday in the US (send help), but elsewhere in the world, brighter colors are in vogue. And in some parts of Eurasia, Neanderthals seemed to prefer manganese-based black pigments, while elsewhere (like Crimea), reds and yellows were all the rage.

“This variability suggests different cultural trajectories, possibly involving community-level traditions, long-distance exchanges, or local innovation,” wrote D’Errico and his colleagues.

The real takeaway here is twofold: First, evidence continues to pile up that Neanderthals were just as smart, innovative, and creative as our species, and they’d developed their own nuanced culture and sophisticated tools long before the first Homo sapiens ventured into Eurasia. And second, the impulse to make art is rooted deep in our family tree.

Science Advances, 2025. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adx4722 (About DOIs).

Edgar Wright’s Explanation for Never Wanting to Make Shaun of the Dead 2 Makes Perfect Sense

Edgar Wright’s Explanation for Never Wanting to Make Shaun of the Dead 2 Makes Perfect Sense