Early Monday morning, a Falcon 9 rocket lifted off from its original launch site in Florida. Remarkably, it was SpaceX's 100th launch of the year.

Perhaps even more notable was the rocket's payload: two-dozen Project Kuiper satellites, which were dispensed into low-Earth orbit on target. This was SpaceX's second launch of satellites for Amazon, which is developing a constellation to deliver low-latency broadband Internet around the world. SpaceX, then, just launched a direct competitor to its Starlink network into orbit. And it was for the founder of Amazon, Jeff Bezos, who owns a rocket company of his own in Blue Origin.

So how did it come to this—Bezos and Elon Musk, competitors in so many ways, working together in space?

Most obvious answer: SpaceX is a launch business

First and foremost, one of SpaceX's two core businesses is launching rockets. (The other is its Starlink Internet service). SpaceX sells launch services to all comers and typically offers the lowest price per kilogram to orbit.

By reusing the first stage of the Falcon 9, SpaceX has cracked the code on rapid, reliable launch service. Launch used to be expensive and rare, and it would take years to get manifested onto a rocket. Because the Falcon 9 now flies so frequently, it provides a relatively fast way to get a payload into space.

SpaceX also has proven that it is willing to launch competitors. Between December 2022 and October 2024, SpaceX launched four batches of satellites for OneWeb, another broadband Internet competitor. AST SpaceMobile has purchased multiple launches from SpaceX for its direct-to-device satellites. The Falcon 9 rocket has also launched two Cygnus spacecraft to the International Space Station for Northrop Grumman, a direct competitor to its Cargo Dragon vehicle.

For SpaceX, this is great business. The company gets to flex its "anti-monopoly" credibility as well as put cash into its pockets. Because the incremental costs of flying a partially reusable Falcon 9 are so low—perhaps as low as $15 million, by some estimates—SpaceX can plow competitors' cash into further development of Starlink or Starship.

Second answer: The satellites are ready, but the rockets are not

So why are competitors willing to pay SpaceX to launch? Over the past five years, a unique set of circumstances has caused the Falcon 9 rocket to be just about the only Western rocket with any spare capacity for launching mass into orbit.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine, and resulting sanctions, took the Proton and Soyuz vehicles off the market for Western satellite companies. SpaceX's main competitor in the United States, United Launch Alliance, has been going through a protracted process of developing the Vulcan rocket, and these delays have slowed the company's flight rate to a trickle. Similarly, both Japan and Europe have been modernizing their launch fleets, and the H3 and Ariane 6 rockets are only getting going now. Finally, at Bezos' Blue Origin launch company, development of the large New Glenn rocket has been slow as well.

In summary, Russia is off the market, and everyone else was going through rocket development hell just as SpaceX hit its stride with the Falcon 9.

This was bad news for Amazon, which reserved launch services on Vulcan, Ariane 6, and New Glenn three years ago. At the time it was not clear whether the rockets would be ready first or if Amazon would get through the difficult period of finalizing its Kuiper satellite design and scaling up production of those spacecraft. Now the answer is known: Amazon has solved its supply chain issues and gotten good at manufacturing Kuiper satellites.

The company presently has about 100 satellites in orbit, and sources report that it continues to manufacture Kuiper spacecraft at that rate with nearly 100 more ready to go. Amazon has a contract for three launches with the Falcon 9 rocket, and it may well extend the agreement depending on the pace at which Vulcan, Ariane 6, and New Glenn can achieve a higher flight cadence.

Less obvious answer: SpaceX gains leverage

SpaceX is also not doing this entirely out of the goodness of its heart. Last year The Wall Street Journal reported, credibly, that SpaceX asked companies seeking launch services, including OneWeb and Kepler Communications, to share spectrum rights as a condition of flying on Falcon 9.

The term spectrum rights refers to using part of the radio frequency spectrum for transmitting data to and from space. The Federal Communications Commission is responsible for assigning rights to use the spectrum in the United States, with other regulatory agencies operating in other nations. SpaceX needs spectrum rights for Starlink as it expands service around the world.

According to The Wall Street Journal report, OneWeb did end up making spectrum concessions to secure the launch slots it needed to complete the initial phase of its constellation after Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

Although the reliance on Falcon 9 may change as the new generation of medium- and heavy lift rockets comes online, satellite consultant Tim Farrar notes that other SpaceX competitors are still facing difficult decisions. For example, Globalstar recently signed a launch deal with SpaceX for replacement satellites. Apple owns a 20 percent stake in Globalstar and is interested in finding a competitor to SpaceX's direct-to-device Internet service. So that agreement was probably at least a little bit uncomfortable.

And looking ahead, other companies, including AST SpaceMobile (which appears to have bet on New Glenn readiness) and EchoStar will need to decide whether to buy from SpaceX or (likely) pay more for slower access to space from other launch companies.

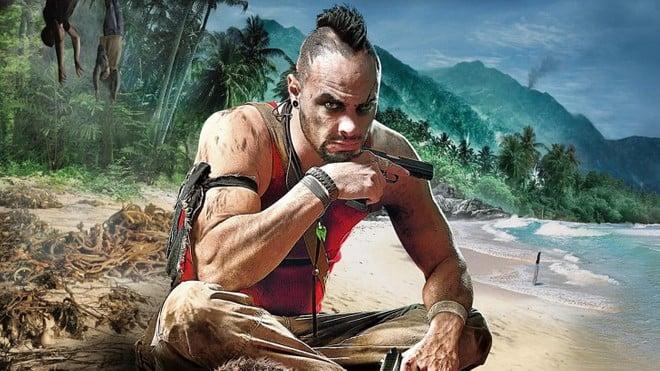

Far Cry diventa serie TV con FX: ecco chi c’è dietro il progetto segreto

Far Cry diventa serie TV con FX: ecco chi c’è dietro il progetto segreto